Manticore

Copperplate engraving by Matthäus Merian.

Courtesy of The Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology[1][2]

The manticore or mantichore (Latin: mantichorās; reconstructed Old Persian: *martyahvārah; Modern Persian: مردخوار mard-khar) is a legendary creature from ancient Persian mythology, similar to the Egyptian sphinx that proliferated in Western European medieval art as well. It has the face of a human, the body of a lion, and the tail of a scorpion or a tail covered in venomous spines similar to porcupine quills. There are some accounts that the spines can be launched like arrows. It eats its victims whole, using its three rows of teeth, and leaves no bones behind. Other accounts also have it sporting the wings of a dragon.

Etymology

[edit]The term manticore descends via Latin mantichorās[3][4] from Ancient Greek μαρτιχόρας (martikhórās).[5] This in turn is a transliteration of an Old Persian compound word consisting of martīya 'man' and xuar- stem, 'to eat' (Mod. Persian: مرد; mard + خوردن; khordan);[a][6][7][8] i.e., man-eater.

The ultimate source of manticore was Ctesias, Greek physician of the Persian court during the Achaemenid dynasty, and is based on the testimonies of his Persian-speaking informants who had travelled to India. Ctesias himself wrote that the martichora (μαρτιχόρα) was its name in Persian, which translated into Greek as androphagon[9] or anthropophagon (ἀνθρωποφάγον),[10] i.e., "man-eater".[11][5][b] But the name was mistranscribed as 'mantichoras' in a faulty copy of Aristotle, through whose works the notion of the manticore was perpetuated across Europe.[13]

Ctesias was also later cited by Pausanias regarding the martichoras or androphagos of India.[14]

Classical literature

[edit]An account of the manticore was given in Ctesias's lost book Indica ("India"), and circulated among Greek writers on natural history, but has survived only in fragments and epitomes preserved by later writers.[15]

Photius's Myriobiblon (or Bibliotheca, 9th century) serves as base text, but Aelian (De Natura Animalium, 3rd century) preserves the same information and more:

The beast's name means "maneater", as already noted.[16][9] Aelian citing Ctesias adds that the Mantichora prefers to hunt humans, lying in wait, taking down even 2, 3 men at a time. And the Indians take their young captive, disabling its tail by crushing it with stone before the growth of sting begins.[9]

Pliny's Aethiopian beasts

[edit]Pliny described the "mantichora" in his Naturalis Historia (c. 77 AD)[17] having relied on a faulty copy of Aristotle's natural history that contained the misspelling ("martikhoras").[13]

Pliny also introduced the confused notion that the manticore might occur in Africa, because he had discussed this and other creatures (such as the yale) within a passage on Aethiopia.[18][19][e] But he also described the crocotta and the mantichora of Aethiopia together, and while the crocotta imitated the voices of men[f] the mantichora of Aethiopia too also mimicked human speech, on authority of Juba II,[21] with a voice like the pipe (panpipe, fistula) mixed with trumpet.[22]

Legacy

[edit]Ctesias purportedly saw a martichora presented to the Persian king by the Indians.[9] The Romanised Greek Pausanias was skeptical and considered it an unreliable exaggerated account of a tiger.[14][13] Apollonius of Tyana also dismissed the mantichore as a tall tale, according to the biography by Philostratus (c. 170–247).[23][24]

Pliny did not share Pausanias' skepticism.[13] And for 1500 years afterwards, it was Pliny's account, also copied by Solinus (2nd century), which was held to be authoritative on matters of natural history whether real or mythological.[13] In the advent of Christianity, writings in the Holy Scripture combined with Plinian-Aristotelian learning gave rise to the Physiologus (also c. 2nd century), which later evolved into the medieval bestiaries[13] some of which contained entries on the manticore.

Medieval sources

[edit]Bestiaries

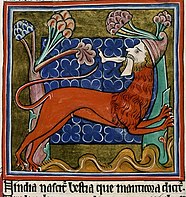

[edit]The manticore has been included in some medieval bestiaries, with accompanying illustrations, though not all.

The thick-maned (and long-bearded) manticore wearing a Phrygian cap is a commonplace design (fig., top left).[27]

In most instances, the manticora is "coloured red or brown and has clawed feet".[28] Artists took the liberty of coloring the manticore blue at times.[29] One example is depicted "as a long-haired blond" (fig., top right).[31] Another has the face of a woman and the body of a blue manticore (fig., bottom right) .[33]

Most manuscripts do not bother detailing the scorpion tail[34] and simply draw a long cat's tail,[28] but in Harley MS 3244 the manticore has an "oddly pointed tail"[34] or an "extraordinary spike on the end" of it,[28] and a tail covered in spikes from end to end is shown on the manticore in several other second family manuscripts.[38][28]

The three-rows of teeth are not faithfully represented except in some third family examples.[28]

Manuscripts and text

[edit]- Second Family

The manticore (Latin: manticora) occurs in about half of the Second Family Latin bestiaries.[30] The specific source used in this case was probably Solinus (2nd century),[39][g]

The text here describing the beast[41][42] differs little from Pliny's Latin version in language,[43] or the Greek version in content (paraphrased above).[44] This is naturally the case, since much of Solinus was recopied out of Pliny.[45][46] The manticora is here described as "bloody-colored" [d] rather than "red like cinnabar".[c][h]

The text concludes by stating that the manticore "seeks human flesh, is active, and leaps so that neither large spaces nor broad obstacles can delay it[42] (neither the broadest space nor the widest barrier can hinder it)".[41]

- H text

Actually there are two candidate sources given for the passage, "Solinus 52.37" and "H iii.8";[47] this "H" being the pseudo-Hugh of Saint Victor De bestiis et aliis rebus, edited by Migne,[48][49] but this source has been regarded circumspectly as the "problematic De bestiis et aliis rebus" by Clark.[50]

- Transitional

The manticore also occurs in the earliest "Transitional" First Family bestiary (c. 1185),[i][30][52] and some Third Family codices as well, whose illustrations attempted to reproduce some of the finer details given in its text.[28]

Confounding with other hybrid beasts

[edit]As aforementioned, the manticore is one of three hybrids from Aithiopia described together by Solinus,[53] appearing in (nearly) successive chapters of the bestiary.[54][j] This created the groundwork for the beasts in adjacent chapters being confounded or amalgamated through scribal errors, as described below in the cases of bestiaries produced in France.

French mistransmission

[edit]The manticore is basically absent from the French bestiary of Pierre de Beauvais,[k] which exist in the short versions of 38 or 39 chapters, and the long version of 71 chapters. Instead, there is a Chapter 44 on the "centicore" (or santicora, var. ceucrocata[55]), which suggests manticore in name, but which is nothing like the standard manticore.[l][56][m] The name is thought to have arisen from misspellings of leucrocotta, compounded by the suffix replaced by -cora by scribal error.[57] Due to further mistransmission, "centicore" became the French misnomer for the yale (eale), a mythic antelope which should be a separate entry in the bestiaries.[59]

Neither manticore nor leucrotta (French: lucrote) appears in Philippe de Thaun's bestiary in Anglo-Norman verse.[60][61][n]

Post-medieval natural history

[edit]

Edward Topsell, in 1607, described the manticore as:

bred among the Indians, having a treble rowe of teeth beneath and above, whose greatnesse, roughnesse, and feete are like a Lyons, his face and eares like unto a mans, his eies grey, and collour red, his taile like the taile of a Scorpion of the earth, armed with a sting, casting forth sharp pointed quills, his voice like the voice of a small trumpet or pipe, being in course as swift as a Hart; His wildnes such as can never be tamed, and his appetite is especially to the flesh of man. His body like the body of a Lyon, being very apt both to leape and to run, so as no distance or space doth hinder him,.. [66][64]

Topsell thought the manticore was described by other names elsewhere. He thought that it was the "same Beast which Avicen calleth Marion, and Maricomorion" and also, the same as the "Leucrocuta, about the bigness of a wilde Ass, being in legs and Hoofs like a Hart, having his mouth reaching on both sides to his ears, and the head and face of a female like unto a Badgers".[64][12]

And Topsell wrote that in India they would "bruise the buttockes and taile" of the whelp or cub they captured, causing it to be incapable of using its quills, thus removing the danger.[64] This differs somewhat from the original sources which stated that they would crush the tail with stone to make them useless.

Heraldry

[edit]The likeness of manticore or similar creatures by another name (i.e. mantyger) have been used in heraldry, spanning from the late High Middle Ages into the modern period.

The mantyger is glossed as merely a variant reading of manticore in the OED,[68] though the 17th century heraldry collector Randle Holme made a fine distinction between manticore and mantyger. Holme's description of the manticore seems to derive directly from naturalist Edward Topsell (cf. above),

[The manticore has] the face of a man, the mouth open to the ears with a treble row of teeth beneath and above; long neck, whose greatness, roughness, body and feet are like a Lyon: of a red colour, his tail like the tail of a Scorpion of the Earth, the end armed with a sting, casting forth sharp pointed quills.[69]

while he describes the mantyger as having

the face and ears of a man, the body of a Tyger, and whole footed like Goose or Dragon; yet others make it with feet like a Tyger,

etc., and also noting that they may be horned or unhorned.[70]

The manticore first appeared in English heraldry in c. 1470, as a badge of William Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings; and in the 16th century.[71]

The mantyger device was later used as a badge by Robert Radcliffe, 1st Earl of Sussex, and by Sir Anthony Babyngton.[71] The Radford[e]'s device was described as "3 mantygers argent" by one source, c. 1600.[72][7] Thus in heraldic discourse the term "manticore" became usurped by "mantyger" during the 17–18th centuries, and "mantiger" in the 19th.[7][o]

It is noted that the manticore/mantiger of heraldic devices has a beast of prey body as standard, but sometimes chosen to be given dragon feet.[7] The Radcliffe family manticore appears to have human feet,[73] and (not so surprisingly), a chronicler described as a "Babyon" (baboon) the device by John Radcliffe (Lord Fitzwater) accompanying Henry VIII into war in France.[74] It has also been speculated the Babyngton device is intended to represent the "Babyon, or baboon, as a play upon his name", and it too also has characteristically "monkey-like feet".[75][p]

The typical heraldic manticore is supposed to have not only the face of an old man, but spiraling horns as well,[7][73][77] although this is not really ascertainable in the Radcliffe family badge, where the purple manticore is wearing a yellow cap[67] (cap of dignity [73]).

Parallels

[edit]Gerald Brenan linked the manticore to the mantequero, a monster feeding on human fat in Andalusian folklore.[78]

The Hindu god Narasimha is often referred to as a Manticore. Narasimha, the man lion, is the fourth avatar of Vishnu and is described as having a man’s torso and the head and claws of a lion.

In fiction

[edit]Dante Alighieri, in his Inferno, depicted the mythical Geryon as having a similar appearance to a manticore, following Pliny's description where it has the face of an honest man, the body of a wyvern, the paws of a lion, and the stinger of a scorpion at the end of its tail.[79]

Fine art

[edit]

The heraldic manticore influenced some Mannerist representations of the sin of Fraud, conceived as a monstrous chimera with a beautiful woman's face – for example, in Bronzino's allegory Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time (National Gallery, London),[80] and more commonly in the decorative schemes called grotteschi (grotesque). From here it passed by way of Cesare Ripa's Iconologia into the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French conception of a sphinx.

Popular culture

[edit]In some modern depictions, such as in the tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) and the card game Magic: The Gathering, manticores are depicted as having wings.[81] They are more specifically given "wings of a dragon" in the implementation of D&D′s 5th edition, according to the Monster Manual (2014),[q][r][83] though an earlier version of the manual described them as "batlike wings".[84]

In the animated sitcom television series Krapopolis, the character of Shlub is depicted as a "mantitaur" which is a half-centaur, half-manticore creature where he was the result of a union between a female centaur and a male manticore. In this show besides the fact that the manticores are depicted with dragon-like wings like other depictions of them, the manticores are shown to have dragon-like horns on their head.[85]

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Early Middle Persian مارتیا mardya "man" (as in human) and خوار khowr- "to eat"

- ^ That mantichora was otherwise known as martiora, "which in the Persian tongue signifieth a devourer of men" was already pointed out by Edward Topsell in 1607.[12] (for further information on Topsell's manticore, cf. infra.

- ^ a b Greek, "red like cinnabar ἐρυθρός ὡς κιννάβαρι"; "light-blue eyes ὀφθαλμοὺς γλαυκοὺς"[16].

- ^ a b Pliny has "eyes light-blue, blood-colored body like a lion oculis glaucis, colore sanguineo, corpore leonis"[22].

- ^ Carl (Karl) Mayhoff (ed., 1857. Plinius Hist. Nat. viii.21., i.e.. Mayhoff ed. (1875), 8.21 (30) §75, p. 74) proposed an emendation of the text eosdem "the same" to apud Indos dein which would qualify the statements to be about India.

- ^ And considered to be based on the [laughing] hyena.[20]

- ^ In the base MS. Add. 11283, the manticore (fol. 8r) and the other hybrids around it has scholia marked "Solinus Cap. 65, p. 244".[40] But these are presumbly later scribal additions, not disclosure of source by the original creators.

- ^ While McCulloch translates literally as "bluish eyes, a lion's body the color of blood", Clark gives the freer translation "green eyes, a russet color lion".

- ^ Morgan Library, MS M.81 (The Worksop Bestiary)] (c. 1185).[51] Recognized in Badke's mss. containing the manticore.[52] Note it is not older than the early Second Family Additional MS 11283.

- ^ XXII. De Cocodrillo (crocodile) intervenes (but this is probably not a hybrid).

- ^ For Pierre de Beauvais's bestiary (in French), the probable direct source was Honorius Augustodunensis which derived from Pliny and Solinus.[55]

- ^ Standard manticore, i.e., such as described in the pseudo Hugo de St. Victor, McCulloch's so-called "H" text, cf. explanatory note, supra.

- ^ At least in the Pierre mss. known in France. But the manticore is included in the Vatican codex of Pierre de Beauvais (longer version) according to Badke.[52]

- ^ Even though Badke lists Philippe de Thaun (MS Cotton Nero A V) as well as a manuscript of Image du Monde (the aforementioned testament to "centicore") as including manticore.[52]

- ^ The corruption of amalgamation of man and tiger suggests false etymology.

- ^ Related to the topic of the heraldic manticore/mantiger exhibiting "baboon" feet, it should be mentioned that there emerged a term "mantegar" meaning a "type of baboon", first attested in 1704.[76] This is also conjectured to derived from corruption of "manticore".[76] As a consequence, the term "mantyger" became an ambiguously variant of "manticore" or "mantegar",[68] after c. 1704, assuming that is the correct approximate dating when the word in that sense was coined.

- ^ Color illustration of the manticore by Jack Stella.[82]

- ^ Another embellished feature of this D&D version is that a "bristling mane stretches down [its] back".[83]

References

[edit]Citations

- ^ Jonston, Johannes (1650). "Titulus I. De Digitatis viviparis Feris. Caput. 1 De Leone.". Historiae naturalis de quadrupetibus. Liber 3. De Quadrupedibus Digitatis Viviparis. engraved by Matthäus Merian. Francofuerti ad Moenum: Impensis hæredum Math. Meriani. pp. 114–124 (p. 124a Tab. LII).

- ^ Enenkel, Karl A. E. [in German] (2014). "Chaper 2: The Species and Beyond: Classification and the Place of Hybrids in Early Modern Zoology". In Enenkel, Karl A. E. [in German]; Smith, Paul J. (eds.). Zoology in Early Modern Culture: Intersections of Science, Theology, Philology, and Political and Religious Education: Intersections of Science, Theology, Philology, and Political and Religious Education. BRILL. pp. 68–70, Fig. 2.4. ISBN 9789004279179.

- ^ Karl Ernst Georges: Ausführliches lateinisch-deutsches Handwörterbuch. 8th ed., Hannover, 1918, vol. 2, col. 802, s.v. mantichorās. ([1])

- ^ Félix Gaffiot: Dictionnaire latin-français. 1934, p. 974. ([2] → [3])

- ^ a b Cf. Henry George Liddell & Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, μαρτιχόρας

- ^ <Old Persian martijaqâra according to the NED, apud McCulloch (1962), p. 142 n103

- ^ a b c d e "manticore". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.); Murray, James A. H. ed. (1908) A New Eng. Dict. VI, s.v."manticore"

- ^ "Manticora" s.v., Eberhart, George M. Mysterious Creatures: A Guide to Cryptozoology. Volume 1: A-M. ABC-Clio/Greenwood. 2002. p. 318. ISBN 1-57607-283-5

- ^ a b c d e Nichols tr. (2013), pp. 61–62. Ctesias Indica Frag. 45dβ Aelian, NA 4.21;

Scholfield, A. F. (tr.) (1918) Characteristics of Animals (Loeb Classical Library); Greek text. - ^ a b Ctesias (1825). "IV Ἐk tων του αυτου: Κτησίου Ἰνδικων Ἐκλογαι (Ex Photii Patriarchae Bibliothec. LXXII, pag. 144 seqq.)". In Baehr, Johann Christian Felix (ed.). Ctesiae Cnidii operum reliquiae. Francofurti ad Moenum: In Officina Broenneriana. pp. 248–249.

- ^ Stoneman, Richard (2021). The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press. pp. 100–101. ISBN 9780691217475.

- ^ a b White [1954] (1984), p. 48n.

- ^ a b c d e f Robinson, Margaret (Winter 1965). "Some Fabulous Beasts". Folklore. 76 (4): 274, 277–278. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1965.9717018. JSTOR 1258298.

- ^ a b Nichols tr. (2013), pp. 62–63. Ctesias Indica Frag. 45dγ. Pausanias 9.21.4.;

Jones, W.H.S.; Ormerod, H.A. (tr.), (1918) Description of Greece, 9.21.4; Greek text - ^ Nichols tr. (2013), p. 11.

- ^ a b c Nichols tr. (2013), pp. 48–49. Ctesias Indica Frag. 45, Photius. Bibliotheca 72.

- ^ mantĭchō^ra. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project. lists Plin. 8, 21, 30, § 75; 8, 30, 45, § 107. So the same passage may be designated variously as 8.21 (30), or 8.30 or 8.75 depending on the editor.

- ^ Nichols tr. (2013), p. 142.

- ^ George, Wilma (1968). "The Yale". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 31: 424. doi:10.2307/750650. JSTOR 750650. S2CID 244492082.

- ^ Bostock, John ed. "Chap. 45. The Crocotta. The Mantichora

- ^ Pliny 8. 107;

Alternatively Pliny NH 8.45.1=Pliny (1938). . Translated by Rackham, Ha.; Jones, W.H.S.; Eichholz, D.E. – via Wikisource.;

Mayhoff ed. (1875), Latin text, p. 82 =e-text@Perseus Project - ^ a b Nichols tr. (2013), p. 63. Ctesias Indica Frag. 45dδ. Pliny 8.75;

Alternatively cited as Pliny NH 8.30=Pliny (1938). . Translated by Rackham, Ha.; Jones, W.H.S.; Eichholz, D.E. – via Wikisource.;

Mayhoff ed. (1875), Latin text, p. 74 =e-text@Perseus Project - ^ Flavius Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana, translated by F. C. Conybeare, volume I, book III. Chapter XLV, pp. 327–329.

And inasmuch as the following conversation also has been recorded by Damis as having been held upon this occasion with regard to the mythological animals and fountains and men met with in India, I must not leave it out, for there is much to be gained by neither believing nor yet disbelieving everything. Accordingly Apollonius asked the question, whether there was there an animal called the man-eater (martichoras); and Iarchas replied: "And what have you heard about the make of this animal? For it is probable that there is some account given of its shape." "There are," replied Apollonius, "tall stories current which I cannot believe; for they say that the creature has four feet, and that his head resembles that of a man, but that in size it is comparable to a lion; while the tail of this animal puts out hairs a cubit long and sharp as thorns, which it shoots like arrows at those who hunt it."

- ^ Nigg (1999), p. 79.

- ^ Wiedl, Birgit (2010). "Chapter 9. Laughing at the Beast: The Judensau". In Classen, Albrecht (ed.). Anti-Jewish Propaganda and Humor from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Period. Walter de Gruyter. p. 333. ISBN 9783110245486.

- ^ "Bodleian Library MS. Bodl. 764". Oxford University, the Bodleian Libraries. Retrieved 2022-09-09., fol. 025r.

- ^ McCulloch (1962), p. 142: "more usual is its depiction as a heavily maned beast having a man's face topped by a Phrygian cap .."; Wiedl (2010): "mid thirteenth-century Salisbury bestiary with its pointed Phrygian hat, long beard and grotesque profile", citing Higgs Strikland, Debra (2003) Saracens, Demons, & Jews, 136, figure 60 and pl.3; Pamela Gravestock, "Did Imaginary Animals Exist?," The Mark of the Beast, p. 121.[25] Both name Bodl. 764 as example.[26]

- ^ a b c d e f George & Yapp (1991), p. 53.

- ^ Rowland, Beryl (2016). "1. The Art of Memory and the Bestiary". In Clark, Willene B.; McMunn, Meradith T. (eds.). Beasts and Birds of the Middle Ages: The Bestiary and Its Legacy. London: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 16. ISBN 1512805513.

- ^ a b c George & Yapp (1991), p. 51.

- ^ Roy.12 F xiii[30]

- ^ Dines, Ilya (2005). "A hitherto unknown bestiary (Paris, BnF, MS Lat. 6838 B)". Rivista di studi testuali. 7: 96.

- ^ BnF Latin 6838 B[32]

- ^ a b McCulloch (1962), p. 142.

- ^ "MS 120: Bestiary". News & Features. University College Oxford. 14 October 2016. Retrieved 2022-09-24. With illustrations of siren and manticore.

- ^ "Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Ashmole 1511, fol. 22v (manticora)". Digital Bodleian. 2017-04-12. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- ^ "Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Douce 151, fol. 18v (manticora)". Digital Bodleian. 2018-01-08. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- ^ University College Library (Oxford), MS. 120,[35] Ashmole 1511, fol. 22v.,[36] Douce 151, ol. 18v.[37]

- ^ Clark (2006), p. 26. Due to the "three Solinus hybrids" being clustered into successive chapters. More on their interrelationships below.

- ^ "British Library Add MS 11283". Bodleian Library MS. Bodl. 764. Retrieved 2022-09-06.. "leucrota (alias lecrocuta)" fol. 7v; "cocodrillus" "manticora" fol. 8r; "parandrum" fol. 8v. Marginal notes indicate Solinus as source.

- ^ a b Clark (2006). "XXIII De manticora/Chapter 23 Manticor", p. 139 (Latin text and English tr.). The base text is British Library MS Add. 11283, dated to 1180s by Clark.

- ^ a b McCulloch (1962) "Manticore", pp. 142–143

- ^ By comparison of Latin texts

- ^ By comparison of English translations

- ^ Clark (2006), p. 26.

- ^ McCulloch (1962), p. 28.

- ^ McCulloch (1962), pp. 142–143.

- ^ McCulloch (1962), p. 31.

- ^ Pseudo-Hugo de St. Vicotor (1854). "De bestiis et aliis rebus III.viii De Manticora". In Migne, J.P. Felix (ed.). Sæculum XI Hugonis de S. Victore.. Opera omnia. Patrologiæ cursus completus. Vol. 3. Paris: Apud Garnieri Fratres. p. 85.

- ^ Clark (2006), p. 13.

- ^ "Workshop Bestiary MS M.81 fols. 38v–39r". Morgan Library and Museum. 27 February 2018. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ a b c d Badke, David (26 August 2022). "Manuscripts: Manticore". The Medieval Bestiary: Animals in the Middle Ages. Retrieved 2022-09-06.

- ^ Clark (2006), p. 26: "three Solinus hybrids"

- ^ Clark (2006), "XXI De leucrotar/Chapter 23 Manticor", p. 139; "XII De crocodrillo/Chapter 22 Crocodile", p. 140; "XXIII De manticora/Chapter 23 Manticor", p. 141; "XXIV De parandro/Chapter 24 Parandrus", p. 141.

- ^ a b c McCulloch (1962), p. 191, n205.

- ^ Académie des inscriptions & belles-lettres (France) (1914). "Titulus I. De Digitatis viviparis Feris. Caput. 1 De Leone.". Histoire littéraire de la France. Vol. 34. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. pp. 385–389.

- ^ The "leucrocota" is given written "ceucocroca" by Honorius, aforementioned as Pierre de Beauvais's source. The ceu- being misread as "cen- in a manuscript" is "not improbable". "And doubtless the ending -ticora was the result of a scribe's attention dropping down a few lines in his source to the word manticora".[55]

- ^ McCulloch (1962), p. 191.

- ^ As according to George C. Druce (1911) McCulloch explains that Gauthier (Gossouin de Metz), in his Image du Monde gave the name "centicore", "leucrota", followed by a chapter on the yale but leaving out a name. This later caused a merge of "centicore" with description of the yale.[58]

- ^ Uhl, Patrice (1999). La constellation poétique du non-sens au moyen âge: onze études sur la poésie fatrasique et ses environs (in French). l'Harmattan. p. 73. ISBN 9782738483485.

- ^ Philip de Thaun (1841). "The Bestiary of Philipee de Thaun". In Wright, Thomas (ed.). Popular Treatises on Science Written During the Middle Ages: In Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norman and English. London: Historical Society of Science. pp. 74–131.. For example, "Cocodrille, p. 85" corresponds to folio 50r of Cotton MS Nero A V digitized @ British Library.

- ^ White [1954] (1984), p. 48 Fig. "The Mantichora".

- ^ Topsell, Edward (1658). The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents. London: E. Cotes, for G. Sawbridge [etc.] pp. 343–345.

- ^ a b c d Topsell (1658) is a two volume in one reprint, with the "§ Mantichora" text and woodcut reprinted in pp. 343–345[63]

- ^ Diekstra, Frans N.M. (1998). Book for a Simple and Devout Woman: A Late Middle English Adaptation of Peraldus's Summa de Vitiis Et Virtutibus and Friar Laurent's Summa Le Roi : Edited from British Library Mss Harley 6571 and Additional 30944. Egbert Forsten. p. 528. ISBN 9789069801155.

- ^ Topsell, Edward (1607). The Historie of Foure-footed Beasts. London. p. 442., quoted from this edition (partly omitted in middle) by Diekstra (1998).[65]

- ^ a b c Thomas Evelyn Scott-Ellis Baron Howard de Walden (1904). Banners, Standards, and Badges: From a Tudor Manuscript in the College of Arms. De Walden Library. pp. 211–212.

- ^ a b "mantyger". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.); Murray, James A. H. ed. (1908) A New Eng. Dict. VI, s.v."mantyger", variant of Mantegar, Manticore.

- ^ Holme, Randle (1688). "Second book, Chapter X, LIII". The Academy of Armorie and Blazon. Chester. p. 212., quoted in Dennys (1975), p. 115.

- ^ Holme (1688), Second book, Chapter IX, XVII-XIX, p. 175, quoted in Dennys (1975), p. 115.

- ^ a b Dennys (1975), pp. 115–116.

- ^ Baring-Gould, Sabine; Twigge, Robert, eds. (1898). An Armory of the Western Counties. J.G. Commin. p. 89., for "Radforde"

- ^ a b c Rothery, Guy Cadogan (1915). A. B. C. of Heraldry. London: Stanley Paul & Co. p. 74.

- ^ Cott. MS. Cleop. C. v. fol. 59.[67]

- ^ Dennys (1975), p. 116.

- ^ a b "mantegar". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.); Murray, James A. H. ed. (1908) A New Eng. Dict. VI, s.v."Mantegar".

- ^ Dennys (1975), pp. 114–117.

- ^ Al Sur de Granada, pages 190-193, Gerald Brenan, 1997, Fábula - Tusquets Editores. Originally South from Granada, 1957

- ^ Dante Alighieri; Grandgent, C. H. (1933). La Divina commedia di Dante Alighieri (in Italian). Boston; New York: D.C. Heath and Co. OCLC 1026178.

Dante's image was profoundly modified, however, by Pliny's description – followed by Solinus – of a strange beast called Mantichora (Historia Naturalis, VIII, 30) which has the face of a man, the body of a lion, and a tail ending in a sting like a scorpion's

- ^ Moffitt, John F. (1996). "An Exemplary Humanist Hybrid: Vasari's "Fraude" with Reference to Bronzino's "Sphinx"". Renaissance Quarterly. 49 (2): 303–333. doi:10.2307/2863160. JSTOR 2863160. S2CID 192984544. traces the chimeric image of Fraud backwards from Bronzino.

- ^ Wood, Juliette (2018). "Ch. 1: When unicorns walked the earth: A brief history of the unicorn and its fellows". Fantastic Creatures in Mythology and Folklore: From Medieval Times to the Present Day. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-3500-5925-2.

- ^ "manticore". Encyclopedia Exandria. 2 August 2022. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ a b Crawford, Jeremy, ed. (July 2003). Monster Manual: Dungeons & Dragons Core Rulebook. Co-lead design by Mike Mearls (5 ed.). Wizards of the Coast. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-7869-6561-8.

- ^ Gygax, Gary (1993). Monstrous Manual. TSR. p. 246. ISBN 9781560766193.

The manticore.. with a leonine torso and legs, batlike wings, am man's head, a tail tipped with iron spikes,.. stns 6 feet at the shoulder and meausres 15 feet in length. It has a 25-foot wingspan

- ^ Bennett, Tara (September 23, 2023). "Krapopolis Review: Beware of Greeks bearing too many poop jokes". IGN.

the monster mantitaur – that's half manticore, half centaur, so human plus lion plus scorpion plus horse – Shlub

Bibliography

- Clark, Willene B. (2006). A Medieval Book of Beasts: The Second-family Bestiary : Commentary, Art, Text and Translation. Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851156828.

- Dennys, Rodney (1975). The Heraldic Imagination. London: Barrie & Jenkins. ISBN 9780214653865. American edition, Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. 1976

- George, Wilma B.; Yapp, William Brunsdon (1991). The Naming of the Beasts: Natural History in the Medieval Bestiary. Duckworth. pp. 51–53. ISBN 9780715622384.

- Ctesias (2013). Ctesias: On India. Translated by Nichols, Andrew. A&C Black. pp. 48–49. ISBN 9781472519979., Aelian, pp. 61–62; Pausanias, pp. 62–63

- Nigg, Joe (1999). The Book of Fabulous Beasts: A Treasury of Writings from Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195095616.

- McCulloch, Florence (1962) [1960]. Mediaeval Latin and French Bestiaries (revised ed.). Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807890332.; [ Reprint], C. N. Potter, 1976

- Pliny (1875). "Liber VIII. §75". Naturalis historiae libri XXXVII 21. (39). Translated by Mayhoff, Carolus [in German]. Lipsiae: In aedibus B.G. Teubneri.

- White, T. H., ed. (1984) [1954]. The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation from a Latin Bestiary of the Twelfth Century. Dover. pp. 48, 51–52, 247, 261. ISBN 9780486246093. Translated from the Latin (Cambridge Univ. Library MS. Ii.4.26).

External links

[edit]- "Manticore". The Medieval Bestiary.

- "Mantikhoras". Theoi Project.