Nitrogen cycle

The nitrogen cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which nitrogen is converted into multiple chemical forms as it circulates among atmospheric, terrestrial, and marine ecosystems. The conversion of nitrogen can be carried out through both biological and physical processes. Important processes in the nitrogen cycle include fixation, ammonification, nitrification, and denitrification. The majority of Earth's atmosphere (78%) is atmospheric nitrogen,[16] making it the largest source of nitrogen. However, atmospheric nitrogen has limited availability for biological use, leading to a scarcity of usable nitrogen in many types of ecosystems.

The nitrogen cycle is of particular interest to ecologists because nitrogen availability can affect the rate of key ecosystem processes, including primary production and decomposition. Human activities such as fossil fuel combustion, use of artificial nitrogen fertilizers, and release of nitrogen in wastewater have dramatically altered the global nitrogen cycle.[17][18][19] Human modification of the global nitrogen cycle can negatively affect the natural environment system and also human health.[20][21]

Processes

| Part of a series on |

| Biogeochemical cycles |

|---|

|

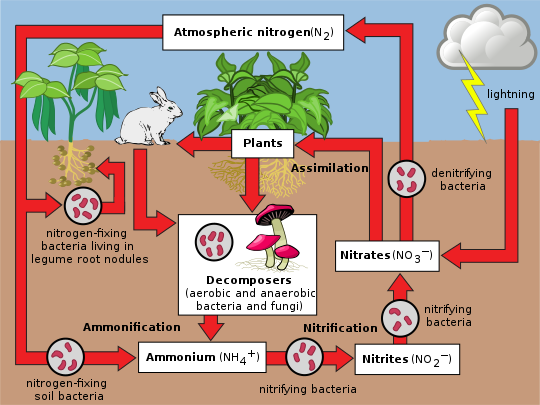

Nitrogen is present in the environment in a wide variety of chemical forms including organic nitrogen, ammonium (NH+4), nitrite (NO−2), nitrate (NO−3), nitrous oxide (N2O), nitric oxide (NO) or inorganic nitrogen gas (N2). Organic nitrogen may be in the form of a living organism, humus or in the intermediate products of organic matter decomposition. The processes in the nitrogen cycle is to transform nitrogen from one form to another. Many of those processes are carried out by microbes, either in their effort to harvest energy or to accumulate nitrogen in a form needed for their growth. For example, the nitrogenous wastes in animal urine are broken down by nitrifying bacteria in the soil to be used by plants. The diagram alongside shows how these processes fit together to form the nitrogen cycle.

Nitrogen fixation

The conversion of nitrogen gas (N2) into nitrates and nitrites through atmospheric, industrial and biological processes is called nitrogen fixation. Atmospheric nitrogen must be processed, or "fixed", into a usable form to be taken up by plants. Between 5 and 10 billion kg per year are fixed by lightning strikes, but most fixation is done by free-living or symbiotic bacteria known as diazotrophs. These bacteria have the nitrogenase enzyme that combines gaseous nitrogen with hydrogen to produce ammonia, which is converted by the bacteria into other organic compounds. Most biological nitrogen fixation occurs by the activity of molybdenum (Mo)-nitrogenase, found in a wide variety of bacteria and some Archaea. Mo-nitrogenase is a complex two-component enzyme that has multiple metal-containing prosthetic groups.[22] An example of free-living bacteria is Azotobacter. Symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria such as Rhizobium usually live in the root nodules of legumes (such as peas, alfalfa, and locust trees). Here they form a mutualistic relationship with the plant, producing ammonia in exchange for carbohydrates. Because of this relationship, legumes will often increase the nitrogen content of nitrogen-poor soils. A few non-legumes can also form such symbioses. Today, about 30% of the total fixed nitrogen is produced industrially using the Haber-Bosch process,[23] which uses high temperatures and pressures to convert nitrogen gas and a hydrogen source (natural gas or petroleum) into ammonia.[24]

Assimilation

Plants can absorb nitrate or ammonium from the soil by their root hairs. If nitrate is absorbed, it is first reduced to nitrite ions and then ammonium ions for incorporation into amino acids, nucleic acids, and chlorophyll. In plants that have a symbiotic relationship with rhizobia, some nitrogen is assimilated in the form of ammonium ions directly from the nodules. It is now known that there is a more complex cycling of amino acids between Rhizobia bacteroids and plants. The plant provides amino acids to the bacteroids so ammonia assimilation is not required and the bacteroids pass amino acids (with the newly fixed nitrogen) back to the plant, thus forming an interdependent relationship.[25] While many animals, fungi, and other heterotrophic organisms obtain nitrogen by ingestion of amino acids, nucleotides, and other small organic molecules, other heterotrophs (including many bacteria) are able to utilize inorganic compounds, such as ammonium as sole N sources. Utilization of various N sources is carefully regulated in all organisms.

Ammonification

When a plant or animal dies or an animal expels waste, the initial form of nitrogen is organic. Bacteria or fungi convert the organic nitrogen within the remains back into ammonium (NH+4), a process called ammonification or mineralization. Enzymes involved are:

- GS: Gln Synthetase (cytosolic & plastic)

- GOGAT: Glu 2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase (Ferredoxin & NADH-dependent)

- GDH: Glu Dehydrogenase:

- Minor role in ammonium assimilation.

- Important in amino acid catabolism.

Nitrification

The conversion of ammonium to nitrate is performed primarily by soil-living bacteria and other nitrifying bacteria. In the primary stage of nitrification, the oxidation of ammonium (NH+4) is performed by bacteria such as the Nitrosomonas species, which converts ammonia to nitrites (NO−2). Other bacterial species such as Nitrobacter, are responsible for the oxidation of the nitrites (NO−2) into nitrates (NO−3). It is important for the ammonia (NH3) to be converted to nitrates or nitrites because ammonia gas is toxic to plants.

Due to their very high solubility and because soils are highly unable to retain anions, nitrates can enter groundwater. Elevated nitrate in groundwater is a concern for drinking water use because nitrate can interfere with blood-oxygen levels in infants and cause methemoglobinemia or blue-baby syndrome.[28] Where groundwater recharges stream flow, nitrate-enriched groundwater can contribute to eutrophication, a process that leads to high algal population and growth, especially blue-green algal populations. While not directly toxic to fish life, like ammonia, nitrate can have indirect effects on fish if it contributes to this eutrophication. Nitrogen has contributed to severe eutrophication problems in some water bodies. Since 2006, the application of nitrogen fertilizer has been increasingly controlled in Britain and the United States. This is occurring along the same lines as control of phosphorus fertilizer, restriction of which is normally considered essential to the recovery of eutrophied waterbodies.

Denitrification

Denitrification is the reduction of nitrates back into nitrogen gas (N

2), completing the nitrogen cycle. This process is performed by bacterial species such as Pseudomonas and Paracoccus, under anaerobic conditions. They use the nitrate as an electron acceptor in the place of oxygen during respiration. These facultatively (meaning optionally) anaerobic bacteria can also live in aerobic conditions. Denitrification happens in anaerobic conditions e.g. waterlogged soils. The denitrifying bacteria use nitrates in the soil to carry out respiration and consequently produce nitrogen gas, which is inert and unavailable to plants. Denitrification occurs in free-living microorganisms as well as obligate symbionts of anaerobic ciliates.[29]

-

Classical representation of nitrogen cycle

-

Flow of nitrogen through the ecosystem. Bacteria are a key element in the cycle, providing different forms of nitrogen compounds able to be assimilated by higher organisms

-

Simple representation of the nitrogen cycle. Blue represent nitrogen storage, green is for processes moving nitrogen from one place to another, and red is for the bacteria involved

Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium

Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA), or nitrate/nitrite ammonification, is an anaerobic respiration process. Microbes which undertake DNRA oxidise organic matter and use nitrate as an electron acceptor, reducing it to nitrite, then ammonium (NO−3 → NO−2 → NH+4).[30] Both denitrifying and nitrate ammonification bacteria will be competing for nitrate in the environment, although DNRA acts to conserve bioavailable nitrogen as soluble ammonium rather than producing dinitrogen gas.[31]

Anaerobic ammonia oxidation

The ANaerobic AMMonia OXidation process is also known as the ANAMMOX process, an abbreviation coined by joining the first syllables of each of these three words. This biological process is a redox comproportionation reaction, in which ammonia (the reducing agent giving electrons) and nitrite (the oxidizing agent accepting electrons) transfer three electrons and are converted into one molecule of diatomic nitrogen (N

2) gas and two water molecules. This process makes up a major proportion of nitrogen conversion in the oceans. The stoichiometrically balanced formula for the ANAMMOX chemical reaction can be written as following, where an ammonium ion includes the ammonia molecule, its conjugated base:

- NH+4 + NO−2 → N2 + 2 H2O (ΔG° = −357 kJ⋅mol−1).[32]

This an exergonic process (here also an exothermic reaction) releasing energy, as indicated by the negative value of ΔG°, the difference in Gibbs free energy between the products of reaction and the reagents.

Other processes

Though nitrogen fixation is the primary source of plant-available nitrogen in most ecosystems, in areas with nitrogen-rich bedrock, the breakdown of this rock also serves as a nitrogen source.[33][34][35] Nitrate reduction is also part of the iron cycle, under anoxic conditions Fe(II) can donate an electron to NO−3 and is oxidized to Fe(III) while NO−3 is reduced to NO−2, N2O, N2, and NH+4 depending on the conditions and microbial species involved.[36] The fecal plumes of cetaceans also act as a junction in the marine nitrogen cycle, concentrating nitrogen in the epipelagic zones of ocean environments before its dispersion through various marine layers, ultimately enhancing oceanic primary productivity.[37]

Marine nitrogen cycle

2 fixation (red), nitrification (light blue), nitrate reduction (violet), DNRA (magenta), denitrification (aquamarine), N-damo (green), and anammox (orange). Black curved arrows represent physical processes such as advection and diffusion.[38]

The nitrogen cycle is an important process in the ocean as well. While the overall cycle is similar, there are different players[40] and modes of transfer for nitrogen in the ocean. Nitrogen enters the water through the precipitation, runoff, or as N

2 from the atmosphere. Nitrogen cannot be utilized by phytoplankton as N

2 so it must undergo nitrogen fixation which is performed predominately by cyanobacteria.[41] Without supplies of fixed nitrogen entering the marine cycle, the fixed nitrogen would be used up in about 2000 years.[42] Phytoplankton need nitrogen in biologically available forms for the initial synthesis of organic matter. Ammonia and urea are released into the water by excretion from plankton. Nitrogen sources are removed from the euphotic zone by the downward movement of the organic matter. This can occur from sinking of phytoplankton, vertical mixing, or sinking of waste of vertical migrators. The sinking results in ammonia being introduced at lower depths below the euphotic zone. Bacteria are able to convert ammonia to nitrite and nitrate but they are inhibited by light so this must occur below the euphotic zone.[43] Ammonification or Mineralization is performed by bacteria to convert organic nitrogen to ammonia. Nitrification can then occur to convert the ammonium to nitrite and nitrate.[44] Nitrate can be returned to the euphotic zone by vertical mixing and upwelling where it can be taken up by phytoplankton to continue the cycle. N

2 can be returned to the atmosphere through denitrification.

Ammonium is thought to be the preferred source of fixed nitrogen for phytoplankton because its assimilation does not involve a redox reaction and therefore requires little energy. Nitrate requires a redox reaction for assimilation but is more abundant so most phytoplankton have adapted to have the enzymes necessary to undertake this reduction (nitrate reductase). There are a few notable and well-known exceptions that include most Prochlorococcus and some Synechococcus that can only take up nitrogen as ammonium.[42]

The nutrients in the ocean are not uniformly distributed. Areas of upwelling provide supplies of nitrogen from below the euphotic zone. Coastal zones provide nitrogen from runoff and upwelling occurs readily along the coast. However, the rate at which nitrogen can be taken up by phytoplankton is decreased in oligotrophic waters year-round and temperate water in the summer resulting in lower primary production.[45] The distribution of the different forms of nitrogen varies throughout the oceans as well.

Nitrate is depleted in near-surface water except in upwelling regions. Coastal upwelling regions usually have high nitrate and chlorophyll levels as a result of the increased production. However, there are regions of high surface nitrate but low chlorophyll that are referred to as HNLC (high nitrogen, low chlorophyll) regions. The best explanation for HNLC regions relates to iron scarcity in the ocean, which may play an important part in ocean dynamics and nutrient cycles. The input of iron varies by region and is delivered to the ocean by dust (from dust storms) and leached out of rocks. Iron is under consideration as the true limiting element to ecosystem productivity in the ocean.

Ammonium and nitrite show a maximum concentration at 50–80 m (lower end of the euphotic zone) with decreasing concentration below that depth. This distribution can be accounted for by the fact that nitrite and ammonium are intermediate species. They are both rapidly produced and consumed through the water column.[42] The amount of ammonium in the ocean is about 3 orders of magnitude less than nitrate.[42] Between ammonium, nitrite, and nitrate, nitrite has the fastest turnover rate. It can be produced during nitrate assimilation, nitrification, and denitrification; however, it is immediately consumed again.

New vs. regenerated nitrogen

Nitrogen entering the euphotic zone is referred to as new nitrogen because it is newly arrived from outside the productive layer.[41] The new nitrogen can come from below the euphotic zone or from outside sources. Outside sources are upwelling from deep water and nitrogen fixation. If the organic matter is eaten, respired, delivered to the water as ammonia, and re-incorporated into organic matter by phytoplankton it is considered recycled/regenerated production.

New production is an important component of the marine environment. One reason is that only continual input of new nitrogen can determine the total capacity of the ocean to produce a sustainable fish harvest.[45] Harvesting fish from regenerated nitrogen areas will lead to a decrease in nitrogen and therefore a decrease in primary production. This will have a negative effect on the system. However, if fish are harvested from areas of new nitrogen the nitrogen will be replenished.

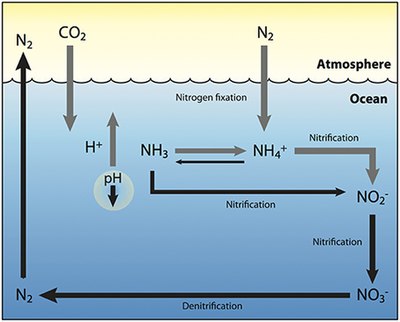

Future acidification

As illustrated by the diagram on the right, additional carbon dioxide (CO2) is absorbed by the ocean and reacts with water, carbonic acid (H

2CO

3) is formed and broken down into both bicarbonate (HCO−3) and hydrogen (H+

) ions (gray arrow), which reduces bioavailable carbonate (CO2−3) and decreases ocean pH (black arrow). This is likely to enhance nitrogen fixation by diazotrophs (gray arrow), which utilize H+

ions to convert nitrogen into bioavailable forms such as ammonia (NH

3) and ammonium ions (NH+4). However, as pH decreases, and more ammonia is converted to ammonium ions (gray arrow), there is less oxidation of ammonia to nitrite (NO–

2), resulting in an overall decrease in nitrification and denitrification (black arrows). This in turn would lead to a further build-up of fixed nitrogen in the ocean, with the potential consequence of eutrophication. Gray arrows represent an increase while black arrows represent a decrease in the associated process.[39]

Human influences on the nitrogen cycle

As a result of extensive cultivation of legumes (particularly soy, alfalfa, and clover), growing use of the Haber–Bosch process in the production of chemical fertilizers, and pollution emitted by vehicles and industrial plants, human beings have more than doubled the annual transfer of nitrogen into biologically available forms.[28] In addition, humans have significantly contributed to the transfer of nitrogen trace gases from Earth to the atmosphere and from the land to aquatic systems. Human alterations to the global nitrogen cycle are most intense in developed countries and in Asia, where vehicle emissions and industrial agriculture are highest.[46]

Generation of Nr, reactive nitrogen, has increased over 10 fold in the past century due to global industrialisation.[2][47] This form of nitrogen follows a cascade through the biosphere via a variety of mechanisms, and is accumulating as the rate of its generation is greater than the rate of denitrification.[48]

Nitrous oxide (N

2O) has risen in the atmosphere as a result of agricultural fertilization, biomass burning, cattle and feedlots, and industrial sources.[49] N

2O has deleterious effects in the stratosphere, where it breaks down and acts as a catalyst in the destruction of atmospheric ozone. Nitrous oxide is also a greenhouse gas and is currently the third largest contributor to global warming, after carbon dioxide and methane. While not as abundant in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, it is, for an equivalent mass, nearly 300 times more potent in its ability to warm the planet.[50]

Ammonia (NH

3) in the atmosphere has tripled as the result of human activities. It is a reactant in the atmosphere, where it acts as an aerosol, decreasing air quality and clinging to water droplets, eventually resulting in nitric acid (HNO3) that produces acid rain. Atmospheric ammonia and nitric acid also damage respiratory systems.

The very high temperature of lightning naturally produces small amounts of NO

x, NH

3, and HNO

3, but high-temperature combustion has contributed to a 6- or 7-fold increase in the flux of NO

x to the atmosphere. Its production is a function of combustion temperature - the higher the temperature, the more NO

x is produced. Fossil fuel combustion is a primary contributor, but so are biofuels and even the burning of hydrogen. However, the rate that hydrogen is directly injected into the combustion chambers of internal combustion engines can be controlled to prevent the higher combustion temperatures that produce NO

x.

Ammonia and nitrous oxides actively alter atmospheric chemistry. They are precursors of tropospheric (lower atmosphere) ozone production, which contributes to smog and acid rain, damages plants and increases nitrogen inputs to ecosystems. Ecosystem processes can increase with nitrogen fertilization, but anthropogenic input can also result in nitrogen saturation, which weakens productivity and can damage the health of plants, animals, fish, and humans.[28]

Decreases in biodiversity can also result if higher nitrogen availability increases nitrogen-demanding grasses, causing a degradation of nitrogen-poor, species-diverse heathlands.[51]

Consequence of human modification of the nitrogen cycle

Impacts on natural systems

Increasing levels of nitrogen deposition is shown to have several adverse effects on both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.[52][53] Nitrogen gases and aerosols can be directly toxic to certain plant species, affecting the aboveground physiology and growth of plants near large point sources of nitrogen pollution. Changes to plant species may also occur as nitrogen compound accumulation increases availability in a given ecosystem, eventually changing the species composition, plant diversity, and nitrogen cycling. Ammonia and ammonium – two reduced forms of nitrogen – can be detrimental over time due to increased toxicity toward sensitive species of plants,[54] particularly those that are accustomed to using nitrate as their source of nitrogen, causing poor development of their roots and shoots. Increased nitrogen deposition also leads to soil acidification, which increases base cation leaching in the soil and amounts of aluminum and other potentially toxic metals, along with decreasing the amount of nitrification occurring and increasing plant-derived litter. Due to the ongoing changes caused by high nitrogen deposition, an environment's susceptibility to ecological stress and disturbance – such as pests and pathogens – may increase, thus making it less resilient to situations that otherwise would have little impact on its long-term vitality.

Additional risks posed by increased availability of inorganic nitrogen in aquatic ecosystems include water acidification; eutrophication of fresh and saltwater systems; and toxicity issues for animals, including humans.[55] Eutrophication often leads to lower dissolved oxygen levels in the water column, including hypoxic and anoxic conditions, which can cause death of aquatic fauna. Relatively sessile benthos, or bottom-dwelling creatures, are particularly vulnerable because of their lack of mobility, though large fish kills are not uncommon. Oceanic dead zones near the mouth of the Mississippi in the Gulf of Mexico are a well-known example of algal bloom-induced hypoxia.[56][57] The New York Adirondack Lakes, Catskills, Hudson Highlands, Rensselaer Plateau and parts of Long Island display the impact of nitric acid rain deposition, resulting in the killing of fish and many other aquatic species.[58]

Ammonia (NH

3) is highly toxic to fish, and the level of ammonia discharged from wastewater treatment facilities must be closely monitored. Nitrification via aeration before discharge is often desirable to prevent fish deaths. Land application can be an attractive alternative to aeration.

Impacts on human health: nitrate accumulation in drinking water

Leakage of Nr (reactive nitrogen) from human activities can cause nitrate accumulation in the natural water environment, which can create harmful impacts on human health. Excessive use of N-fertilizer in agriculture has been a significant source of nitrate pollution in groundwater and surface water.[59][60] Due to its high solubility and low retention by soil, nitrate can easily escape from the subsoil layer to the groundwater, causing nitrate pollution. Some other non-point sources for nitrate pollution in groundwater originate from livestock feeding, animal and human contamination, and municipal and industrial waste. Since groundwater often serves as the primary domestic water supply, nitrate pollution can be extended from groundwater to surface and drinking water during potable water production, especially for small community water supplies, where poorly regulated and unsanitary waters are used.[61]

The WHO standard for drinking water is 50 mg NO−3 L−1 for short-term exposure, and for 3 mg NO−3 L−1 chronic effects.[62] Once it enters the human body, nitrate can react with organic compounds through nitrosation reactions in the stomach to form nitrosamines and nitrosamides, which are involved in some types of cancers (e.g., oral cancer and gastric cancer).[63]

Impacts on human health: air quality

Human activities have also dramatically altered the global nitrogen cycle by producing nitrogenous gases associated with global atmospheric nitrogen pollution. There are multiple sources of atmospheric reactive nitrogen (Nr) fluxes. Agricultural sources of reactive nitrogen can produce atmospheric emission of ammonia (NH3), nitrogen oxides (NO

x) and nitrous oxide (N

2O). Combustion processes in energy production, transportation, and industry can also form new reactive nitrogen via the emission of NO

x, an unintentional waste product. When those reactive nitrogens are released into the lower atmosphere, they can induce the formation of smog, particulate matter, and aerosols, all of which are major contributors to adverse health effects on human health from air pollution.[64] In the atmosphere, NO

2 can be oxidized to nitric acid (HNO

3), and it can further react with NH

3 to form ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3), which facilitates the formation of particulate nitrate. Moreover, NH

3 can react with other acid gases (sulfuric and hydrochloric acids) to form ammonium-containing particles, which are the precursors for the secondary organic aerosol particles in photochemical smog.[65]

See also

- Planetary boundaries – Limits not to be exceeded if humanity wants to survive in a safe ecosystem

- Phosphorus cycle – Biogeochemical cycle

References

- ^ Fowler, David; Coyle, Mhairi; Skiba, Ute; Sutton, Mark A.; Cape, J. Neil; Reis, Stefan; Sheppard, Lucy J.; Jenkins, Alan; Grizzetti, Bruna; Galloway, JN; Vitousek, P; Leach, A; Bouwman, AF; Butterbach-Bahl, K; Dentener, F; Stevenson, D; Amann, M; Voss, M (5 July 2013). "The global nitrogen cycle in the twenty-first century". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 368 (1621): 20130164. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0164. PMC 3682748. PMID 23713126.

- ^ a b Galloway, J. N.; Townsend, A. R.; Erisman, J. W.; Bekunda, M.; Cai, Z.; Freney, J. R.; Martinelli, L. A.; Seitzinger, S. P.; Sutton, M. A. (2008). "Transformation of the Nitrogen Cycle: Recent Trends, Questions, and Potential Solutions" (PDF). Science. 320 (5878): 889–892. Bibcode:2008Sci...320..889G. doi:10.1126/science.1136674. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18487183. S2CID 16547816. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-11-08. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- ^ Vitousek, P. M.; Menge, D. N. L.; Reed, S. C.; Cleveland, C. C. (2013). "Biological nitrogen fixation: rates, patterns and ecological controls in terrestrial ecosystems". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 368 (1621): 20130119. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0119. PMC 3682739. PMID 23713117.

- ^ a b Voss, M.; Bange, H. W.; Dippner, J. W.; Middelburg, J. J.; Montoya, J. P.; Ward, B. (2013). "The marine nitrogen cycle: recent discoveries, uncertainties and the potential relevance of climate change". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 368 (1621): 20130121. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0121. PMC 3682741. PMID 23713119.

- ^ a b Fowler, David; Coyle, Mhairi; Skiba, Ute; Sutton, Mark A.; Cape, J. Neil; Reis, Stefan; Sheppard, Lucy J.; Jenkins, Alan; Grizzetti, Bruna; Galloway, JN; Vitousek, P; Leach, A; Bouwman, AF; Butterbach-Bahl, K; Dentener, F; Stevenson, D; Amann, M; Voss, M (5 July 2013). "The global nitrogen cycle in the twenty-first century". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 368 (1621): 20130164. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0164. PMC 3682748. PMID 23713126.

- ^ Vuuren, Detlef P van; Bouwman, Lex F; Smith, Steven J; Dentener, Frank (2011). "Global projections for anthropogenic reactive nitrogen emissions to the atmosphere: an assessment of scenarios in the scientific literature". Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 3 (5): 359–369. Bibcode:2011COES....3..359V. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2011.08.014. hdl:1874/314192. ISSN 1877-3435. S2CID 154935568.

- ^ Pilegaard, K. (2013). "Processes regulating nitric oxide emissions from soils". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 368 (1621): 20130126. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0126. PMC 3682746. PMID 23713124.

- ^ Levy, H.; Moxim, W. J.; Kasibhatla, P. S. (1996). "A global three-dimensional time-dependent lightning source of tropospheric NOx". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 101 (D17): 22911–22922. Bibcode:1996JGR...10122911L. doi:10.1029/96jd02341. ISSN 0148-0227.

- ^ Sutton, M. A.; Reis, S.; Riddick, S. N.; Dragosits, U.; Nemitz, E.; Theobald, M. R.; Tang, Y. S.; Braban, C. F.; Vieno, M. (2013). "Towards a climate-dependent paradigm of ammonia emission and deposition". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 368 (1621): 20130166. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0166. PMC 3682750. PMID 23713128.

- ^ Dentener, F.; Drevet, J.; Lamarque, J. F.; Bey, I.; Eickhout, B.; Fiore, A. M.; Hauglustaine, D.; Horowitz, L. W.; Krol, M. (2006). "Nitrogen and sulfur deposition on regional and global scales: a multimodel evaluation" (PDF). Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 20 (4): n/a. Bibcode:2006GBioC..20.4003D. doi:10.1029/2005GB002672. S2CID 839759.

- ^ a b c Duce, R. A.; LaRoche, J.; Altieri, K.; Arrigo, K. R.; Baker, A. R.; Capone, D. G.; Cornell, S.; Dentener, F.; Galloway, J. (2008). "Impacts of Atmospheric Anthropogenic Nitrogen on the Open Ocean". Science. 320 (5878): 893–7. Bibcode:2008Sci...320..893D. doi:10.1126/science.1150369. hdl:21.11116/0000-0001-CD7A-0. PMID 18487184. S2CID 11204131.

- ^ Bouwman, L.; Goldewijk, K. K.; Van Der Hoek, K. W.; Beusen, A. H. W.; Van Vuuren, D. P.; Willems, J.; Rufino, M. C.; Stehfest, E. (2011-05-16). "Exploring global changes in nitrogen and phosphorus cycles in agriculture induced by livestock production over the 1900-2050 period". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (52): 20882–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012878108. PMC 3876211. PMID 21576477.

- ^ Solomon, Susan (2007). Climate change 2007 : the physical science basis. Published for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [by] Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521880091. OCLC 228429704.

- ^ Sutton, Mark A., ed. (2011-04-14). The European nitrogen assessment : sources, effects, and policy perspectives. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107006126. OCLC 690090202.

- ^ Deutsch, Curtis; Sarmiento, Jorge L.; Sigman, Daniel M.; Gruber, Nicolas; Dunne, John P. (2007). "Spatial coupling of nitrogen inputs and losses in the ocean". Nature. 445 (7124): 163–167. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..163D. doi:10.1038/nature05392. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17215838. S2CID 10804715.

- ^ Steven B. Carroll; Steven D. Salt (2004). Ecology for gardeners. Timber Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-88192-611-8.

- ^ Kuypers, MMM; Marchant, HK; Kartal, B (2011). "The Microbial Nitrogen-Cycling Network". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 1 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2018.9. hdl:21.11116/0000-0003-B828-1. PMID 29398704. S2CID 3948918.

- ^ Galloway, J. N.; et al. (2004). "Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future generations". Biogeochemistry. 70 (2): 153–226. doi:10.1007/s10533-004-0370-0. S2CID 98109580.

- ^ Reis, Stefan; Bekunda, Mateete; Howard, Clare M; Karanja, Nancy; Winiwarter, Wilfried; Yan, Xiaoyuan; Bleeker, Albert; Sutton, Mark A (2016-12-01). "Synthesis and review: Tackling the nitrogen management challenge: from global to local scales". Environmental Research Letters. 11 (12): 120205. Bibcode:2016ERL....11l0205R. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/12/120205. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ^ Gu, Baojing; Ge, Ying; Ren, Yuan; Xu, Bin; Luo, Weidong; Jiang, Hong; Gu, Binhe; Chang, Jie (2012-08-17). "Atmospheric Reactive Nitrogen in China: Sources, Recent Trends, and Damage Costs". Environmental Science & Technology. 46 (17): 9420–9427. Bibcode:2012EnST...46.9420G. doi:10.1021/es301446g. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 22852755.

- ^ Kim, Haryun; Lee, Kitack; Lim, Dhong-Il; Nam, Seung-Il; Kim, Tae-Wook; Yang, Jin-Yu T.; Ko, Young Ho; Shin, Kyung-Hoon; Lee, Eunil (2017-05-11). "Widespread Anthropogenic Nitrogen in Northwestern Pacific Ocean Sediment". Environmental Science & Technology. 51 (11): 6044–52. Bibcode:2017EnST...51.6044K. doi:10.1021/acs.est.6b05316. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 28462990.

- ^ Moir, JWB, ed. (2011). Nitrogen Cycling in Bacteria: Molecular Analysis. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-86-8.

- ^ Smith, B.; Richards, R.L.; Newton, W.E. (2013) [2004]. Catalysts for nitrogen fixation: nitrogenases, relevant chemical models and commercial processes. Kluwer. ISBN 9781402036118.

- ^ Smil, V (1997). Cycles of Life. Scientific American Library. ISBN 9780716750796.

- ^ Willey, Joanne M. (2011). Prescott's Microbiology (8th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 705. ISBN 978-0-07-337526-7.

- ^ Sparacino-Watkins, Courtney; Stolz, John F.; Basu, Partha (2013-12-16). "Nitrate and periplasmic nitrate reductases". Chem. Soc. Rev. 43 (2): 676–706. doi:10.1039/c3cs60249d. PMC 4080430. PMID 24141308.

- ^ Simon, Jörg; Klotz, Martin G. (2013). "Diversity and evolution of bioenergetic systems involved in microbial nitrogen compound transformations". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1827 (2): 114–135. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.07.005. PMID 22842521.

- ^ a b c Vitousek, PM; Aber, J; Howarth, RW; Likens, GE; Matson, PA; Schindler, DW; Schlesinger, WH; Tilman, GD (1997). "Human alteration of the global nitrogen cycle: Sources and consequences" (PDF). Ecological Applications. 1 (3): 1–17. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(1997)007[0737:HAOTGN]2.0.CO;2. hdl:1813/60830. ISSN 1051-0761.

- ^ Graf, Jon S.; Schorn, Sina; Kitzinger, Katharina; Ahmerkamp, Soeren; Woehle, Christian; Huettel, Bruno; Schubert, Carsten J.; Kuypers, Marcel M. M.; Milucka, Jana (3 March 2021). "Anaerobic endosymbiont generates energy for ciliate host by denitrification". Nature. 591 (7850): 445–450. Bibcode:2021Natur.591..445G. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03297-6. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 7969357. PMID 33658719.

- ^ Lam, Phyllis; Kuypers, Marcel M.M. (2011). "Microbial Nitrogen Processes in Oxygen Minimum Zones". Annual Review of Marine Science. 3: 317–345. Bibcode:2011ARMS....3..317L. doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142814. hdl:21.11116/0000-0001-CA25-2. PMID 21329208.

- ^ Marchant, H.K.; Lavik, G.; Holtappels, M.; Kuypers, M.M.M. (2014). "The Fate of Nitrate in Intertidal Permeable Sediments". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e104517. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j4517M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104517. PMC 4134218. PMID 25127459.

- ^ "Anammox". Anammox - MicrobeWiki. MicrobeWiki. Archived from the original on 2015-09-27. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ "Nitrogen Study Could 'Rock' A Plant's World". NPR.org. 2011-09-06. Archived from the original on 2011-12-05. Retrieved 2011-10-22.

- ^ Schuur, E. A. G. (2011). "Ecology: Nitrogen from the deep". Nature. 477 (7362): 39–40. Bibcode:2011Natur.477...39S. doi:10.1038/477039a. PMID 21886152. S2CID 2946571.

- ^ Morford, S. L.; Houlton, B. Z.; Dahlgren, R. A. (2011). "Increased forest ecosystem carbon and nitrogen storage from nitrogen rich bedrock". Nature. 477 (7362): 78–81. Bibcode:2011Natur.477...78M. doi:10.1038/nature10415. PMID 21886160. S2CID 4352571.

- ^ Burgin, Amy J.; Yang, Wendy H.; Hamilton, Stephen K.; Silver, Whendee L. (2011). "Beyond carbon and nitrogen: how the microbial energy economy couples elemental cycles in diverse ecosystems". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 9 (1): 44–52. Bibcode:2011FrEE....9...44B. doi:10.1890/090227. hdl:1808/21008. ISSN 1540-9309.

- ^ Roman, J.; McCarthy, J.J. (2010). "The Whale Pump: Marine Mammals Enhance Primary Productivity in a Coastal Basin". PLOS ONE. 5 (10): e13255. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513255R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013255. PMC 2952594. PMID 20949007.

- ^ Pajares Moreno, S.; Ramos, R. (2019). "Processes and Microorganisms Involved in the Marine Nitrogen Cycle: Knowledge and Gaps". Frontiers in Marine Science. 6: 739. doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00739.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ a b O'Brien, Paul A.; Morrow, Kathleen M.; Willis, Bette L.; Bourne, David G. (2016). "Implications of Ocean Acidification for Marine Microorganisms from the Free-Living to the Host-Associated". Frontiers in Marine Science. 3. doi:10.3389/fmars.2016.00047.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Moulton, Orissa M; Altabet, Mark A; Beman, J Michael; Deegan, Linda A; Lloret, Javier; Lyons, Meaghan K; Nelson, James A; Pfister, Catherine A (May 2016). "Microbial associations with macrobiota in coastal ecosystems: patterns and implications for nitrogen cycling". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 14 (4): 200–8. Bibcode:2016FrEE...14..200M. doi:10.1002/fee.1262. hdl:1912/8083. ISSN 1540-9295.

- ^ a b Miller, Charles (2008). Biological Oceanography. Blackwell. pp. 60–62. ISBN 978-0-632-05536-4.

- ^ a b c d Gruber, Nicolas (2008). Nitrogen in the Marine Environment. Elsevier. pp. 1–35. ISBN 978-0-12-372522-6.

- ^ Miller, Charles (2008). Biological oceanography. Blackwell. pp. 60–62. ISBN 978-0-632-05536-4.

- ^ Boyes, Elliot, Susan, Michael. "Learning Unit: Nitrogen Cycle Marine Environment". Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lalli, Parsons, Carol, Timothy (1997). Biological oceanography: An introduction. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-3384-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Holland, Elisabeth A.; Dentener, Frank J.; Braswell, Bobby H.; Sulzman, James M. (1999). "Contemporary and pre-industrial global reactive nitrogen budgets". Biogeochemistry. 46 (1–3): 7. Bibcode:1999Biogc..46....7H. doi:10.1007/BF01007572. S2CID 189917368.

- ^ Gu, Baojing; Ge, Ying; Ren, Yuan; Xu, Bin; Luo, Weidong; Jiang, Hong; Gu, Binhe; Chang, Jie (2012-09-04). "Atmospheric Reactive Nitrogen in China: Sources, Recent Trends, and Damage Costs". Environmental Science & Technology. 46 (17): 9420–7. Bibcode:2012EnST...46.9420G. doi:10.1021/es301446g. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 22852755.

- ^ Cosby, B. Jack; Cowling, Ellis B.; Howarth, Robert W.; Seitzinger, Sybil P.; Erisman, Jan Willem; Aber, John D.; Galloway, James N. (2003-04-01). "The Nitrogen Cascade". BioScience. 53 (4): 341–356. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[0341:TNC]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0006-3568. S2CID 3356400.

- ^ Chapin, S.F.; Matson, P.A.; Mooney, H.A. (2002). Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology. Springer. p. 345. ISBN 0-387-95443-0.

- ^ Proceedings of the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE) International Biofuels Project Rapid Assessment, 22–25 September 2008, Gummersbach, Germany, R. W. Howarth and S. Bringezu, editors. 2009 Executive Summary, p. 3 Archived 2009-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Aerts, Rien & Berendse, Frank (1988). "The Effect of Increased Nutrient Availability on Vegetation Dynamics in Wet Heathlands". Vegetatio. 76 (1/2): 63–69. doi:10.1007/BF00047389. JSTOR 20038308. S2CID 34882407.

- ^ Bobbink, R.; Hicks, K.; Galloway, J.; Spranger, T.; Alkemade, R.; Ashmore, M.; Bustamante, M.; Cinderby, S.; Davidson, E. (2010-01-01). "Global assessment of nitrogen deposition effects on terrestrial plant diversity: a synthesis" (PDF). Ecological Applications. 20 (1): 30–59. Bibcode:2010EcoAp..20...30B. doi:10.1890/08-1140.1. ISSN 1939-5582. PMID 20349829. S2CID 4792945. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-09-30. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- ^ Liu, Xuejun; Duan, Lei; Mo, Jiangming; Du, Enzai; Shen, Jianlin; Lu, Xiankai; Zhang, Ying; Zhou, Xiaobing; He, Chune (2011). "Nitrogen deposition and its ecological impact in China: An overview". Environmental Pollution. 159 (10): 2251–2264. Bibcode:2011EPoll.159.2251L. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2010.08.002. PMID 20828899.

- ^ Britto, Dev T.; Kronzucker, Herbert J. (2002). "NH4+ toxicity in higher plants: a critical review". Journal of Plant Physiology. 159 (6): 567–584. doi:10.1078/0176-1617-0774.

- ^ Camargoa, Julio A.; Alonso, Álvaro (2006). "Ecological and toxicological effects of inorganic nitrogen pollution in aquatic ecosystems: A global assessment". Environment International. 32 (6): 831–849. Bibcode:2006EnInt..32..831C. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2006.05.002. hdl:10261/294824. PMID 16781774.

- ^ Rabalais, Nancy N.; Turner, R. Eugene; Wiseman, William J. Jr. (2002). "Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia, aka "The Dead Zone"". Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 33 (1): 235–63. Bibcode:2002AnRES..33..235R. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150513. JSTOR 3069262.

- ^ Dybas, Cheryl Lyn. (2005). "Dead Zones Spreading in World Oceans". BioScience. 55 (7): 552–557. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[0552:DZSIWO]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ New York State Environmental Conservation, Environmental Impacts of Acid Deposition: Lakes [1] Archived 2010-11-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Power, J.F.; Schepers, J.S. (1989). "Nitrate contamination of groundwater in North America". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 26 (3–4): 165–187. Bibcode:1989AgEE...26..165P. doi:10.1016/0167-8809(89)90012-1. ISSN 0167-8809.

- ^ Strebel, O.; Duynisveld, W.H.M.; Böttcher, J. (1989). "Nitrate pollution of groundwater in western Europe". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 26 (3–4): 189–214. Bibcode:1989AgEE...26..189S. doi:10.1016/0167-8809(89)90013-3. ISSN 0167-8809.

- ^ Fewtrell, Lorna (2004). "Drinking-Water Nitrate, Methemoglobinemia, and Global Burden of Disease: A Discussion". Environmental Health Perspectives. 112 (14): 1371–4. Bibcode:2004EnvHP.112.1371F. doi:10.1289/ehp.7216. PMC 1247562. PMID 15471727.

- ^ Global Health Observatory : (GHO). World Health Organization. OCLC 50144984.

- ^ Canter, Larry W. (2019-01-22), "Illustrations of Nitrate Pollution of Groundwater", Nitrates in Groundwater, Routledge, pp. 39–71, doi:10.1201/9780203745793-3, ISBN 9780203745793, S2CID 133944481

- ^ Kampa, Marilena; Castanas, Elias (2008). "Human health effects of air pollution". Environmental Pollution. 151 (2): 362–367. Bibcode:2008EPoll.151..362K. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.012. PMID 17646040. S2CID 38513536.

- ^ Erisman, J. W.; Galloway, J. N.; Seitzinger, S.; Bleeker, A.; Dise, N. B.; Petrescu, A. M. R.; Leach, A. M.; de Vries, W. (2013-05-27). "Consequences of human modification of the global nitrogen cycle". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 368 (1621): 20130116. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0116. PMC 3682738. PMID 23713116.