Mescaline

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Mescalin; Mezcalin; Mezcaline; 3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenethylamine; 3,4,5-TMPEA; TMPEA |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | mescaline |

| Routes of administration | Oral, smoking, insufflation, intravenous[1][2] |

| Drug class | Serotonin receptor agonist; Serotonergic psychedelic; Hallucinogen |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Oxidative deamination, N-acetylation, O-demethylation, conjugation, other pathways[4][5] |

| Metabolites | • 3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl-acetaldehyde[4][1] • 3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenylacetic acid[1] • 3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenylethanol[5] • Others[4][5][2] |

| Onset of action | Oral: 0.5–3 hours[6][1][2] |

| Elimination half-life | 3.6 hours[6][7] |

| Duration of action | ≥10–12 hours[6][1][2] |

| Excretion | Urine (28–81% unchanged, 13–26% as TMPA)[1][4][5][2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.174 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C11H17NO3 |

| Molar mass | 211.261 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.067 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 35 to 36 °C (95 to 97 °F) |

| Boiling point | 180 °C (356 °F) at 12 mmHg |

| Solubility in water | moderately soluble in water mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

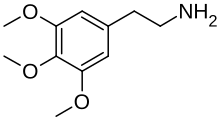

Mescaline, also known as mescalin or mezcalin,[8] and in chemical terms 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine, is a naturally occurring psychedelic protoalkaloid of the substituted phenethylamine class, known for its hallucinogenic effects comparable to those of LSD and psilocybin.[4][1][6][5] It binds to and activates certain serotonin receptors in the brain, producing hallucinogenic effects.[1][6]

Biological sources

[edit]It occurs naturally in several species of cacti. It is also reported to be found in small amounts in certain members of the bean family, Fabaceae, including Senegalia berlandieri (syn. Acacia berlandieri),[9] although these reports have been challenged and have been unsupported in any additional analyses.[10]

| Plant source | Amount of mescaline (% of dry weight) |

|---|---|

| Echinopsis lageniformis (Bolivian torch cactus, syns. Echinopsis scopulicola, Trichocereus bridgesii)[11] | Average 0.56; 0.85 in one cultivar of Echinopsis scopulicola[11][12] |

| Leucostele terscheckii (syns Echinopsis terscheckii, Trichocereus terscheckii)[13] | 0.005 - 2.375[14][15] |

| Peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii)[16] | 0.01-5.5[17] |

| Trichocereus macrogonus var. macrogonus (Peruvian torch, syns Echinopsis peruviana, Trichocereus peruvianus)[18] | 0.01-0.05;[14] 0.24-0.81[12] |

| Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi (San Pedro cactus, syns Echinopsis pachanoi, Echinopsis santaensis, Trichocereus pachanoi)[19] | 0.23-4.7;[12] 0.32 under its synonym Echinopsis santaensis[12] |

| Trichocereus uyupampensis (syn. Echinopsis uyupampensis) | 0.05[12] |

| Trichocereus tacaquirensis (subsp. taquimbalensis syn. Trichocereus taquimbalensis) | 0.005-2.7[20] |

As shown in the accompanying table, the concentration of mescaline in different specimens can vary largely within a single species. Moreover, the concentration of mescaline within a single specimen varies as well.[21]

History and use

[edit]Peyote has been used for at least 5,700 years by Indigenous peoples of the Americas in Mexico.[2][22] Europeans recorded use of peyote in Native American religious ceremonies upon early contact with the Huichol people in Mexico.[23] Other mescaline-containing cacti such as the San Pedro have a long history of use in South America, from Peru to Ecuador.[24][25][26][27] While religious and ceremonial peyote use was widespread in the Aztec Empire and northern Mexico at the time of the Spanish conquest, religious persecution confined it to areas near the Pacific coast and up to southwest Texas. However, by 1880, peyote use began to spread north of South-Central America with "a new kind of peyote ceremony" inaugurated by the Kiowa and Comanche people. These religious practices, incorporated legally in the United States in 1920 as the Native American Church, have since spread as far as Saskatchewan, Canada.[22]

In traditional peyote preparations, the top of the cactus is cut off, leaving the large tap root along with a ring of green photosynthesizing area to grow new heads. These heads are then dried to make disc-shaped buttons. Buttons are chewed to produce the effects or soaked in water to drink. However, the taste of the cactus is bitter, so modern users will often grind it into a powder and pour it into capsules to avoid having to taste it. The typical dosage is 200–400 milligrams of mescaline sulfate or 178–356 milligrams of mescaline hydrochloride.[28][29] The average 76 mm (3.0 in) peyote button contains about 25 mg mescaline.[30] Some analyses of traditional preparations of San Pedro cactus have found doses ranging from 34 mg to 159 mg of total alkaloids, a relatively low and barely psychoactive amount. It appears that patients who receive traditional treatments with San Pedro ingest sub-psychoactive doses and do not experience psychedelic effects.[31]

Botanical studies of peyote began in the 1840s and the drug was listed in the Mexican pharmacopeia.[5] The first of mescal buttons was published by John Raleigh Briggs in 1887.[5] Mescaline was first isolated and identified in 1896 or 1897 by the German chemist Arthur Heffter and his colleagues.[5][2][32] He showed that mescaline was exclusively responsible for the psychoactive or hallucinogenic effects of peyote.[5] However, other components of peyote, such as hordenine, pellotine, and anhalinine, are also active.[5] Mescaline was first synthesized in 1919 by Ernst Späth.[2][33]

In 1955, English politician Christopher Mayhew took part in an experiment for BBC's Panorama, in which he ingested 400 mg of mescaline under the supervision of psychiatrist Humphry Osmond. Though the recording was deemed too controversial and ultimately omitted from the show, Mayhew praised the experience, calling it "the most interesting thing I ever did".[34]

Studies of the potential therapeutic effects of mescaline started in the 1950s.[5]

The mechanism of action of mescaline, activation of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, became known in the 1990s.[5]

Potential medical usage

[edit]Mescaline has a wide array of suggested medical usage, including treatment of depression, anxiety, PTSD,[35] and alcoholism.[36] However, its status as a Schedule I controlled substance in the Convention on Psychotropic Substances limits availability of the drug to researchers. Because of this, very few studies concerning mescaline's activity and potential therapeutic effects in people have been conducted since the early 1970s.[37][38][39]

Behavioral and non-behavioral effects

[edit]Mescaline induces a psychedelic state comparable to those produced by LSD and psilocybin, but with unique characteristics.[39] Subjective effects may include altered thinking processes, an altered sense of time and self-awareness, and closed- and open-eye visual phenomena.[40]

Prominence of color is distinctive, appearing brilliant and intense. Recurring visual patterns observed during the mescaline experience include stripes, checkerboards, angular spikes, multicolor dots, and very simple fractals that turn very complex. The English writer Aldous Huxley described these self-transforming amorphous shapes as like animated stained glass illuminated from light coming through the eyelids in his autobiographical book The Doors of Perception (1954). Like LSD, mescaline induces distortions of form and kaleidoscopic experiences but they manifest more clearly with eyes closed and under low lighting conditions.[41]

Heinrich Klüver coined the term "cobweb figure" in the 1920s to describe one of the four form constant geometric visual hallucinations experienced in the early stage of a mescaline trip: "Colored threads running together in a revolving center, the whole similar to a cobweb". The other three are the chessboard design, tunnel, and spiral. Klüver wrote that "many 'atypical' visions are upon close inspection nothing but variations of these form-constants."[42]

As with LSD, synesthesia can occur especially with the help of music.[43] An unusual but unique characteristic of mescaline use is the "geometrization" of three-dimensional objects. The object can appear flattened and distorted, similar to the presentation of a Cubist painting.[44]

Mescaline elicits a pattern of sympathetic arousal, with the peripheral nervous system being a major target for this substance.[43]

According to a research project in the Netherlands, ceremonial San Pedro use seems to be characterized by relatively strong spiritual experiences, and low incidence of challenging experiences.[45]

Chemistry

[edit]Mescaline, also known as 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine (3,4,5-TMPEA), is a substituted phenethylamine derivative.[46][5] It is closely structurally related to the catecholamine neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine.[46]

The drug is relatively hydrophilic with low fat solubility.[5] Its predicted log P (XLogP3) is 0.7.[46]

Biosynthesis

[edit]Mescaline is biosynthesized from tyrosine, which, in turn, is derived from phenylalanine by the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase. In Lophophora williamsii (Peyote), dopamine converts into mescaline in a biosynthetic pathway involving m-O-methylation and aromatic hydroxylation.[47]

Tyrosine and phenylalanine serve as metabolic precursors towards the synthesis of mescaline. Tyrosine can either undergo a decarboxylation via tyrosine decarboxylase to generate tyramine and subsequently undergo an oxidation at carbon 3 by a monophenol hydroxylase or first be hydroxylated by tyrosine hydroxylase to form L-DOPA and decarboxylated by DOPA decarboxylase. These create dopamine, which then experiences methylation by a catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) by an S-adenosyl methionine (SAM)-dependent mechanism. The resulting intermediate is then oxidized again by a hydroxylase enzyme, likely monophenol hydroxylase again, at carbon 5, and methylated by COMT. The product, methylated at the two meta positions with respect to the alkyl substituent, experiences a final methylation at the 4 carbon by a guaiacol-O-methyltransferase, which also operates by a SAM-dependent mechanism. This final methylation step results in the production of mescaline.

Phenylalanine serves as a precursor by first being converted to L-tyrosine by L-amino acid hydroxylase. Once converted, it follows the same pathway as described above.[48][49]

Laboratory synthesis

[edit]

Mescaline was first synthesized in 1919 by Ernst Späth from 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl chloride.[33] Several approaches using different starting materials have been developed since, including the following:

- Hofmann rearrangement of 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenylpropionamide.[51]

- Cyanohydrin reaction between potassium cyanide and 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde followed by acetylation and reduction.[52][53]

- Henry reaction of 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde with nitromethane followed by nitro compound reduction of ω-nitrotrimethoxystyrene.[54][55][56][57][58][59][60]

- Ozonolysis of elemicin followed by reductive amination.[61]

- Ester reduction of Eudesmic acid's methyl ester followed by halogenation, Kolbe nitrile synthesis, and nitrile reduction.[62][63][64]

- Amide reduction of 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenylacetamide.[65]

- Reduction of 3,4,5-trimethoxy(2-nitrovinyl)benzene with lithium aluminum hydride.[40]

- Treatment of tricarbonyl-(η6-1,2,3-trimethoxybenzene) chromium complex with acetonitrile carbanion in THF and iodine, followed by reduction of the nitrile with lithium aluminum hydride.[62]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]| Target | Affinity (Ki, nM) |

|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 1,841–4,600 |

| 5-HT1B | >10,000 |

| 5-HT1D | >10,000 |

| 5-HT1E | 5,205 |

| 5-HT1F | ND |

| 5-HT2A | 550–17,400 (Ki) 88–10,000 (EC50) 56–107% (Emax) |

| 5-HT2B | 793–800 (Ki) >20,000 (EC50) |

| 5-HT2C | 300–17,000 20–114 (EC50) 22–95% (Emax) |

| 5-HT3 | >10,000 |

| 5-HT4 | ND |

| 5-HT5A | >10,000 |

| 5-HT6 | >10,000 |

| 5-HT7 | >10,000 |

| α1A | >15,000 |

| α1B | >10,000 |

| α1D | ND |

| α2A | 1,400–8,930 |

| α2B | >10,000 |

| α2C | 745 |

| β1–β2 | >10,000 |

| D1 | >10,000 |

| D2 | >10,000 |

| D3 | >17,000 |

| D4 | >10,000 |

| D5 | >10,000 |

| H1–H4 | >10,000 |

| M1–M5 | >10,000 |

| TAAR1 | 3,300 (Ki) (rat) 11,000 (Ki) (mouse) 3,700–4,800 (EC50) (rodent) >10,000 (EC50) (human) |

| I1 | 2,678 |

| σ1–σ2 | >10,000 |

| SERT | >30,000 (Ki) 367,000 (IC50) |

| NET | >30,000 (Ki) >900,000 (IC50) |

| DAT | >30,000 (Ki) 841,000 (IC50) |

| Notes: The smaller the value, the more avidly the drug binds to the site. All proteins are human unless otherwise specified. Refs: [66][67][6][1] [68][69][70][71][72] | |

In plants, mescaline may be the end-product of a pathway utilizing catecholamines as a method of stress response, similar to how animals may release such compounds and others such as cortisol when stressed. The in vivo function of catecholamines in plants has not been investigated, but they may function as antioxidants, as developmental signals, and as integral cell wall components that resist degradation from pathogens. The deactivation of catecholamines via methylation produces alkaloids such as mescaline.[48]

In humans, mescaline acts similarly to other psychedelic agents.[73] It acts as an agonist,[74] binding to and activating the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.[75][76] Its EC50 at the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor is approximately 10,000 nM and at the serotonin 5-HT2B receptor is greater than 20,000 nM.[1] How activating the 5-HT2A receptor leads to psychedelic effects is still unknown, but it is likely that somehow it involves excitation of neurons in the prefrontal cortex.[77] In addition to the serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptors, mescaline is also known to bind to the serotonin 5-HT2C receptor and a number of other targets.[1][70][68][78]

Mescaline lacks affinity for the monoamine transporters, including the serotonin transporter (SERT), norepinephrine transporter (NET), and dopamine transporter (DAT) (Ki > 30,000 nM).[1] However, it has been found to increase levels of the major serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) at high doses in rodents.[1][5][2][79] This finding suggests that mescaline might inhibit the reuptake and/or induce the release of serotonin at such doses.[1][5][80] However, this possibility has not yet been further assessed or demonstrated.[1] Besides serotonin, mescaline might also weakly induce the release of dopamine, but this is probably of modest significance, if it occurs.[5][2][81] In accordance, there is no evidence of the drug showing addiction or dependence.[2][5] Other psychedelic phenethylamines, including the closely related 2C, DOx, and TMA drugs, are inactive as monoamine releasing agents and reuptake inhibitors.[82][83] However, an exception is trimethoxyamphetamine (TMA), the amphetamine analogue of mescaline, which is a very low-potency serotonin releasing agent (EC50 = 16,000 nM).[82] The possible monoamine-releasing effects of mescaline would likely be related to its structural similarity to substituted amphetamines and related compounds.[2][5]

Tolerance to mescaline builds with repeated usage, lasting for a few days. The drug causes cross-tolerance with other serotonergic psychedelics such as LSD and psilocybin.[84]

The LD50 of mescaline has been measured in various animals: 212–315 mg/kg i.p. (mice), 132–410 mg/kg i.p. (rats), 328 mg/kg i.p. (guinea pigs), 54 mg/kg in dogs, and 130 mg/kg i.v. in rhesus macaques.[2][85] For humans, the LD50 of mescaline has been reported to be approximately 880 mg/kg.[85] It has been said that it would be very difficult to consume enough mescaline to cause death in humans.[2]

Mescaline is a relatively low-potency psychedelic, with active doses in the hundreds of milligrams and micromolar affinities for the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.[4][1] For comparison, psilocybin is approximately 20-fold more potent (doses in the tens of milligrams) and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) is approximately 2,000-fold more potent (doses in the tens to hundreds of micrograms).[1] There have been efforts to develop more potent analogues of mescaline.[4] Difluoromescaline and trifluoromescaline are more potent than mescaline, as is its amphetamine homologue TMA.[86][87] Escaline and proscaline are also both more potent than mescaline, showing the importance of the 4-position substituent with regard to receptor binding.[88]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]About half the initial dosage is excreted after 6 hours, but some studies suggest that it is not metabolized at all before excretion. Mescaline appears not to be subject to metabolism by CYP2D6[89] and between 20% and 50% of mescaline is excreted in the urine unchanged, with the rest being excreted as the deaminated-oxidised-carboxylic acid form of mescaline, a likely result of monoamine oxidase (MAO) degradation.[90] However, the enzymes mediating the oxidative deamination of mescaine are controversial.[2] MAO, diamine oxidase (DAO), and/or other enzymes may be involved or responsible.[2]

The previously reported elimination half-life of mescaline was originally reported to be 6 hours, but a new study published in 2023 reported a half-life of 3.6 hours.[7][76] The higher estimate is believed to be due to small sample numbers and collective measurement of mescaline metabolites.[7]

Mescaline appears to have relatively poor blood–brain barrier permeability due to its low lipophilicity.[5][2] However, it is still able to cross into the central nervous system and produce psychoactive effects at sufficienty high doses.[5][2]

Active metabolites of mescaline may contribute to its psychoactive effects.[5][2]

Legal status

[edit]United States

[edit]In the United States, mescaline was made illegal in 1970 by the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act, categorized as a Schedule I hallucinogen.[91] The drug is prohibited internationally by the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[92] Mescaline is legal only for certain religious groups (such as the Native American Church by the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978) and in scientific and medical research. In 1990, the Supreme Court ruled that the state of Oregon could ban the use of mescaline in Native American religious ceremonies. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) in 1993 allowed the use of peyote in religious ceremony, but in 1997, the Supreme Court ruled that the RFRA is unconstitutional when applied against states.[citation needed] Many states, including the state of Utah, have legalized peyote usage with "sincere religious intent", or within a religious organization,[citation needed] regardless of race.[93] Synthetic mescaline, but not mescaline derived from cacti, was officially decriminalized in the state of Colorado by ballot measure Proposition 122 in November 2022.[94]

While mescaline-containing cacti of the genus Echinopsis are technically controlled substances under the Controlled Substances Act, they are commonly sold publicly as ornamental plants.[95]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, mescaline in purified powder form is a Class A drug. However, dried cactus can be bought and sold legally.[96]

Australia

[edit]Mescaline is considered a schedule 9 substance in Australia under the Poisons Standard (February 2020).[97] A schedule 9 substance is classified as "Substances with a high potential for causing harm at low exposure and which require special precautions during manufacture, handling or use. These poisons should be available only to specialised or authorised users who have the skills necessary to handle them safely. Special regulations restricting their availability, possession, storage or use may apply."[97]

Other countries

[edit]In Canada, France, The Netherlands and Germany, mescaline in raw form and dried mescaline-containing cacti are considered illegal drugs. However, anyone may grow and use peyote, or Lophophora williamsii, as well as Echinopsis pachanoi and Echinopsis peruviana without restriction, as it is specifically exempt from legislation.[16] In Canada, mescaline is classified as a schedule III drug under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, whereas peyote is exempt.[98]

In Russia mescaline, its derivatives and mescaline-containing plants are banned as narcotic drugs (Schedule I).[99]

Notable users

[edit]- Salvador Dalí experimented with mescaline believing it would enable him to use his subconscious to further his art potential

- Antonin Artaud wrote 1947's The Peyote Dance, where he describes his peyote experiences in Mexico a decade earlier.[100]

- Jerry Garcia took peyote prior to forming The Grateful Dead but later switched to LSD and DMT since they were easier on the stomach.

- Allen Ginsberg took peyote. Part II of his poem "Howl" was inspired by a peyote vision that he had in San Francisco.[101]

- Ken Kesey took peyote prior to writing One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

- Jean-Paul Sartre took mescaline shortly before the publication of his first book, L'Imaginaire; he had a bad trip during which he imagined that he was menaced by sea creatures. For many years following this, he persistently thought that he was being followed by lobsters, and became a patient of Jacques Lacan in hopes of being rid of them. Lobsters and crabs figure in his novel Nausea.

- Havelock Ellis was the author of one of the first written reports to the public about an experience with mescaline (1898).[102][103][104]

- Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Polish writer, artist and philosopher, experimented with mescaline and described his experience in a 1932 book Nikotyna Alkohol Kokaina Peyotl Morfina Eter.[105]

- Aldous Huxley described his experience with mescaline in the essay "The Doors of Perception" (1954).

- Jim Carroll in The Basketball Diaries described using peyote that a friend smuggled from Mexico.

- Quanah Parker, appointed by the federal government as principal chief of the entire Comanche Nation, advocated the syncretic Native American Church alternative, and fought for the legal use of peyote in the movement's religious practices.

- Hunter S. Thompson wrote an extremely detailed account of his first use of mescaline in "First Visit with Mescalito", and it appeared in his book Songs of the Doomed, as well as featuring heavily in his novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

- Psychedelic research pioneer Alexander Shulgin said he was first inspired to explore psychedelic compounds by a mescaline experience.[106] In 1974, Shulgin synthesized 2C-B, a psychedelic phenylethylamine derivative, structurally similar to mescaline,[107] and one of Shulgin's self-rated most important phenethylamine compounds together with Mescaline, 2C-E, 2C-T-7, and 2C-T-2.[108]

- Bryan Wynter produced Mars Ascends after trying the substance for the first time.[109]

- George Carlin mentioned mescaline use during his youth while being interviewed in 2008.[110]

- Carlos Santana told about his mescaline use in a 1989 Rolling Stone interview.[111]

- Disney animator Ward Kimball described participating in a study of mescaline and peyote conducted by UCLA in the 1960s.[112]

- Michael Cera used real mescaline for the movie Crystal Fairy & the Magical Cactus, as expressed in an interview.[113]

- Philip K. Dick was inspired to write Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said after taking mescaline.[114]

- Arthur Kleps, a psychologist turned drug legalization advocate and writer whose Neo-American Church defended use of marijuana and hallucinogens such as LSD and peyote for spiritual enlightenment and exploration, bought, in 1960, by mail from Delta Chemical Company in New York 1 g of mescaline sulfate and took 500 mg. He experienced a psychedelic trip that caused profound changes in his life and outlook.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- List of psychedelic plants

- Methallylescaline

- Psychedelic experience

- Psychoactive drug

- Entheogen

- The Doors of Perception

- Mind at Large (concept in The Doors of Perception)

- The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Vamvakopoulou IA, Narine KA, Campbell I, Dyck JR, Nutt DJ (January 2023). "Mescaline: The forgotten psychedelic". Neuropharmacology. 222: 109294. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2022.109294. PMID 36252614.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Dinis-Oliveira RJ, Pereira CL, da Silva DD (2019). "Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Aspects of Peyote and Mescaline: Clinical and Forensic Repercussions". Curr Mol Pharmacol. 12 (3): 184–194. doi:10.2174/1874467211666181010154139. PMC 6864602. PMID 30318013.

- ^ Anvisa (24 July 2023). "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 25 July 2023). Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cassels BK, Sáez-Briones P (October 2018). "Dark Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Mescaline". ACS Chem Neurosci. 9 (10): 2448–2458. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00215. PMID 29847089.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Doesburg-van Kleffens M, Zimmermann-Klemd AM, Gründemann C (December 2023). "An Overview on the Hallucinogenic Peyote and Its Alkaloid Mescaline: The Importance of Context, Ceremony and Culture". Molecules. 28 (24): 7942. doi:10.3390/molecules28247942. PMC 10746114. PMID 38138432.

- ^ a b c d e f Holze F, Singh N, Liechti ME, D'Souza DC (May 2024). "Serotonergic Psychedelics: A Comparative Review of Efficacy, Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Binding Profile". Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 9 (5): 472–489. doi:10.1016/j.bpsc.2024.01.007. PMID 38301886.

- ^ a b c Ley L, Holze F, Arikci D, Becker AM, Straumann I, Klaiber A, et al. (October 2023). "Comparative acute effects of mescaline, lysergic acid diethylamide, and psilocybin in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study in healthy participants". Neuropsychopharmacology. 48 (11): 1659–1667. doi:10.1038/s41386-023-01607-2. PMC 10517157. PMID 37231080.

- ^ "Mescaline". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Forbes TD, Clement BA. "Chemistry of Acacia's from South Texas" (PDF). Texas A&M Agricultural Research & Extension Center at Uvalde. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2011.

- ^ "Acacia species with data conflicts". sacredcacti.com. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ a b Bury B (2 August 2021). "Could Synthetic Mescaline Protect Declining Peyote Populations?". Chacruna. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Ogunbodede O, McCombs D, Trout K, Daley P, Terry M (September 2010). "New mescaline concentrations from 14 taxa/cultivars of Echinopsis spp. (Cactaceae) ("San Pedro") and their relevance to shamanic practice". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 131 (2). Elsevier BV: 356–362. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.07.021. PMID 20637277.

- ^ "Cardon Grande (Echinopsis terscheckii)". Desert-tropicals.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Partial List of Alkaloids in Trichocereus Cacti". Thennok.org. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ "Forbidden Fruit Archives". Archived from the original on 28 November 2005.

- ^ a b Drug Identification Bible. Grand Junction, CO: Amera-Chem, Inc. 2007. ISBN 978-0-9635626-9-2.

- ^ Klein MT, Kalam M, Trout K, Fowler N, Terry M (2015). "Mescaline Concentrations in Three Principal Tissues of Lophophora williamsii (Cactaceae): Implications for Sustainable Harvesting Practices". Haseltonia. 131 (2). Elsevier BV: 34–42. doi:10.2985/026.020.0107. S2CID 32474292.

- ^ Ogunbodede O, McCombs D, Trout K, Daley P, Terry M (September 2010). "New mescaline concentrations from 14 taxa/cultivars of Echinopsis spp. (Cactaceae) ("San Pedro") and their relevance to shamanic practice". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 131 (2): 356–362. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.07.021. PMID 20637277.

- ^ Crosby DM, McLaughlin JL (December 1973). "Cactus alkaloids. XIX. Crystallization of mescaline HCl and 3-methoxytyramine HCl from Trichocereus pachanoi" (PDF). Lloydia. 36 (4): 416–418. PMID 4773270. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ "Mescaline in Trichocereus". The Mescaline Garden. Archived from the original on 8 August 2024. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ Van Der Sypt F (3 April 2022). "Validation and exploratory application of a simple, rapid and economical procedure (MESQ) for the quantification of mescaline in fresh cactus tissue and aqueous cactus extracts". PhytoChem & BioSub Journal. doi:10.5281/zenodo.6409376.

- ^ a b El-Seedi HR, De Smet PA, Beck O, Possnert G, Bruhn JG (October 2005). "Prehistoric peyote use: alkaloid analysis and radiocarbon dating of archaeological specimens of Lophophora from Texas". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 101 (1–3): 238–242. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.022. PMID 15990261.

- ^ Ruiz de Alarcón H (1984). Treatise on the Heathen Superstitions that Today Live Among the Indians Native to this New Spain, 1629. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806120317.

- ^ Socha DM, Sykutera M, Orefici G (1 December 2022). "Use of psychoactive and stimulant plants on the south coast of Peru from the Early Intermediate to Late Intermediate Period". Journal of Archaeological Science. 148: 105688. Bibcode:2022JArSc.148j5688S. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2022.105688. ISSN 0305-4403. S2CID 252954052.

- ^ Bussmann RW, Sharon D (November 2006). "Traditional medicinal plant use in Northern Peru: tracking two thousand years of healing culture". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2: 47. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-2-47. PMC 1637095. PMID 17090303.

- ^ Armijos C, Cota I, González S (February 2014). "Traditional medicine applied by the Saraguro yachakkuna: a preliminary approach to the use of sacred and psychoactive plant species in the southern region of Ecuador". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 10: 26. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-10-26. PMC 3975971. PMID 24565054.

- ^ Samorini G (1 June 2019). "The oldest archeological data evidencing the relationship of Homo sapiens with psychoactive plants: A worldwide overview". Journal of Psychedelic Studies. 3 (2): 63–80. doi:10.1556/2054.2019.008. S2CID 135116632.

- ^ "#96 M – Mescaline (3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenethylamine)". PIHKAL. Erowid.org. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Uthaug MV, Davis AK, Haas TF, Davis D, Dolan SB, Lancelotta R, et al. (March 2022). "The epidemiology of mescaline use: Pattern of use, motivations for consumption, and perceived consequences, benefits, and acute and enduring subjective effects". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 36 (3): 309–320. doi:10.1177/02698811211013583. PMC 8902264. PMID 33949246.

- ^ Giannini AJ, Slaby AE, Giannini MC (1982). Handbook of Overdose and Detoxification Emergencies. New Hyde Park, NY.: Medical Examination Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87488-182-0.

- ^ "San Pedro: Basic Info". ICEERS. 20 September 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Arthur Heffter". Character Vaults. Erowid.org. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ a b Späth E (February 1919). "Über dieAnhalonium-Alkaloide I. Anhalin und Mezcalin". Monatshefte für Chemie und Verwandte Teile Anderer Wissenschaften (in German). 40 (2): 129–154. doi:10.1007/BF01524590. ISSN 0343-7329. S2CID 104408477.

- ^ "Panorama: The Mescaline Experiment". February 2005. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012.

- ^ Agin-Liebes G, Haas TF, Lancelotta R, Uthaug MV, Ramaekers JG, Davis AK (April 2021). "Naturalistic Use of Mescaline Is Associated with Self-Reported Psychiatric Improvements and Enduring Positive Life Changes". ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science. 4 (2): 543–552. doi:10.1021/acsptsci.1c00018. PMC 8033766. PMID 33860184.

- ^ "Could LSD treat alcoholism?". abcnews.go.com. 9 March 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ Carpenter DE (8 July 2021). "Mescaline is Resurgent (Yet Again) As a Potential Medicine". Lucid News. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Agin-Liebes G, Haas TF, Lancelotta R, Uthaug MV, Ramaekers JG, Davis AK (April 2021). "Naturalistic Use of Mescaline Is Associated with Self-Reported Psychiatric Improvements and Enduring Positive Life Changes". ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science. 4 (2): 543–552. doi:10.1021/acsptsci.1c00018. PMC 8033766. PMID 33860184.

- ^ a b Bender E (September 2022). "Finding medical value in mescaline". Nature. 609 (7929): S90 – S91. Bibcode:2022Natur.609S..90B. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-02873-8. PMID 36171368. S2CID 252548055.

- ^ a b Kovacic P, Somanathan R (1 January 2009). "Novel, unifying mechanism for mescaline in the central nervous system: electrochemistry, catechol redox metabolite, receptor, cell signaling and structure activity relationships". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2 (4): 181–190. doi:10.4161/oxim.2.4.9380. PMC 2763256. PMID 20716904.

- ^ Freye E, et al. (Joseph V. Levy) (2009). Pharmacology and Abuse of Cocaine, Amphetamines, Ecstasy and Related Designer Drugs: A Comprehensive Review on their Mode of Action, Treatment of Abuse and Intoxication. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 227. ISBN 978-90-481-2447-3.

- ^ A Dictionary of Hallucations. Oradell, NJ.: Springer. 2010. p. 102.

- ^ a b Diaz J (1996). How Drugs Influence Behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-02-328764-0.

- ^ Giannini AJ, Slaby AE (1989). Drugs of Abuse. Oradell, NJ.: Medical Economics Books. pp. 207–239. ISBN 978-0-87489-499-8.

- ^ Bohn A, Kiggen MH, Uthaug MV, van Oorsouw KI, Ramaekers JG, van Schie HT (5 December 2022). "Altered States of Consciousness During Ceremonial San Pedro Use". The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 33 (4): 309–331. doi:10.1080/10508619.2022.2139502. hdl:2066/285968. ISSN 1050-8619.

- ^ a b c "Mescaline". PubChem. Retrieved 6 November 2024.

- ^ Dewick PM (2009). Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach. United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 335–336. ISBN 978-0-471-49641-0.

- ^ a b Kulma A, Szopa J (March 2007). "Catecholamies are active compounds in plants". Plant Science. 172 (3): 433–440. Bibcode:2007PlnSc.172..433K. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2006.10.013.

- ^ Rosengarten H, Friedhoff AJ (1976). "A review of recent studies of the biosynthesis and excretion of hallucinogens formed by methylation of neurotransmitters or related substances". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2 (1): 90–105. doi:10.1093/schbul/2.1.90. PMID 779022.

- ^ "Mescaline : D M Turner". www.mescaline.com.

- ^ Slotta KH, Heller H (1930). "Über β-Phenyl-äthylamine, I. Mitteil.: Mezcalin und mezcalin-ähnliche Substanzen". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (A and B Series). 63 (11): 3029–3044. doi:10.1002/cber.19300631117.

- ^ Amos D (1964). "Preparation of Mescaline from Eucalypt Lignin". Australian Journal of Pharmacy. 49: 529.

- ^ Kindler K, Peschke W (1932). "Über neue und über verbesserte Wege zum Aufbau von pharmakologisch wichtigen Aminen VI. Über Synthesen des Meskalins". Archiv der Pharmazie. 270 (7): 410–413. doi:10.1002/ardp.19322700709. S2CID 93188741.

- ^ Benington F, Morin R (1951). "An Improved Synthesis of Mescaline". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (3): 1353. Bibcode:1951JAChS..73Q1353B. doi:10.1021/ja01147a505.

- ^ Shulgin A, Shulgin A (1991). PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story. Lafayette, CA: Transform Press. p. 703. ISBN 9780963009609.

- ^ Hahn G, Rumpf F (1938). "Über β-[Oxy-phenyl]-äthylamine und ihre Umwandlungen, V. Mitteil.: Kondensation von Oxyphenyl-äthylaminen mit α-Ketonsäuren". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (A and B Series). 71 (10): 2141–2153. doi:10.1002/cber.19380711022.

- ^ Toshitaka O, Hiroaka A (1992). "Synthesis of Phenethylamine Derivatives as Hallucinogen" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 38 (6): 571–580. doi:10.1248/jhs1956.38.571. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ Ramirez F, Erne M (1950). "Über die Reduktion von β-Nitrostyrolen mit Lithiumaluminiumhydrid". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 33 (4): 912–916. doi:10.1002/hlca.19500330420.

- ^ Szyszka G, Slotta KH (1933). "Über β-Phenyl-äthylamine.III. Mitteilung: Neue Darstellung von Mescalin". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 137 (9–12): 339–350. doi:10.1002/prac.19331370907.

- ^ Burger A, Ramirez FA (1950). "The Reduction of Phenolic β-Nitrostyrenes by Lithium Aluminum Hydride". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 72 (6): 2781–2782. Bibcode:1950JAChS..72.2781R. doi:10.1021/ja01162a521.

- ^ Hahn G, Wassmuth H (1934). "Über β-[Oxyphenyl]-äthylamine und ihre Umwandlungen, I. Mitteil.: Synthese des Mezcalins". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (A and B Series). 67 (4): 696–708. doi:10.1002/cber.19340670430.

- ^ a b Makepeace T (1951). "A New Synthesis of Mescaline". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 71 (11): 5495–5496. Bibcode:1951JAChS..73.5495T. doi:10.1021/ja01155a562.

- ^ Dornow A, Petsch G (1952). "Über die Darstellung des Oxymezcalins und Mezcalins 2. Mitteilung". Archiv der Pharmazie. 285 (7): 323–326. doi:10.1002/ardp.19522850704. S2CID 97553172.

- ^ Ikan R (1991). Natural Products: A Laboratory Guide 2nd Ed. San Diego: Academic Press, Inc. pp. 232–235. ISBN 978-0123705518.

- ^ Banholzer K, Campbell TW, Schmid H (1952). "Notiz über eine neue Synthese von Mezcalin, N-Methyl- und N-Dimethylmezcalin". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 35 (5): 1577–1581. doi:10.1002/hlca.19520350519.

- ^ "PDSP Database". UNC (in Zulu). Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ Liu T. "BindingDB BDBM50059891 1-amino-2-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)ethane::2-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)ethanamine::3,4,5-trimethoxybenzeneethanamine::3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine::3,4,5-trimethoxyphenylethylamine::CHEMBL26687::Mescalin::Meskalin::TMPEA::US20240166618, Compound Mescaline::mescalina::mescaline::mezcalina". BindingDB. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ a b Ray TS (February 2010). "Psychedelics and the human receptorome". PLOS ONE. 5 (2): e9019. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9019R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009019. PMC 2814854. PMID 20126400.

- ^ Rickli A, Luethi D, Reinisch J, Buchy D, Hoener MC, Liechti ME (December 2015). "Receptor interaction profiles of novel N-2-methoxybenzyl (NBOMe) derivatives of 2,5-dimethoxy-substituted phenethylamines (2C drugs)" (PDF). Neuropharmacology. 99: 546–553. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.034. PMID 26318099.

- ^ a b Rickli A, Moning OD, Hoener MC, Liechti ME (August 2016). "Receptor interaction profiles of novel psychoactive tryptamines compared with classic hallucinogens" (PDF). European Neuropsychopharmacology. 26 (8): 1327–1337. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.05.001. PMID 27216487. S2CID 6685927.

- ^ Gainetdinov RR, Hoener MC, Berry MD (July 2018). "Trace Amines and Their Receptors". Pharmacol Rev. 70 (3): 549–620. doi:10.1124/pr.117.015305. PMID 29941461.

- ^ Simmler LD, Buchy D, Chaboz S, Hoener MC, Liechti ME (April 2016). "In Vitro Characterization of Psychoactive Substances at Rat, Mouse, and Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 357 (1): 134–144. doi:10.1124/jpet.115.229765. PMID 26791601.

- ^ Nichols DE (February 2004). "Hallucinogens". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 101 (2): 131–181. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.11.002. PMID 14761703.

- ^ Appel JB, Callahan PM (January 1989). "Involvement of 5-HT receptor subtypes in the discriminative stimulus properties of mescaline". European Journal of Pharmacology. 159 (1): 41–46. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(89)90041-1. PMID 2707301.

- ^ Monte AP, Waldman SR, Marona-Lewicka D, Wainscott DB, Nelson DL, Sanders-Bush E, et al. (September 1997). "Dihydrobenzofuran analogues of hallucinogens. 4. Mescaline derivatives". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 40 (19): 2997–3008. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.9370. doi:10.1021/jm970219x. PMID 9301661.

- ^ a b Klaiber A, Schmid Y, Becker AM, Straumann I, Erne L, Jelusic A, et al. (September 2024). "Acute dose-dependent effects of mescaline in a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy subjects". Translational Psychiatry. 14 (1): 395. doi:10.1038/s41398-024-03116-2. PMC 11442856. PMID 39349427.

- ^ Béïque JC, Imad M, Mladenovic L, Gingrich JA, Andrade R (June 2007). "Mechanism of the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor-mediated facilitation of synaptic activity in prefrontal cortex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (23): 9870–9875. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.9870B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700436104. PMC 1887564. PMID 17535909.

- ^ "Neuropharmacology of Hallucinogens". Erowid.org. 27 March 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Freedman DX, Gottlieb R, Lovell RA (1970). "Psychotomimetic drugs and brain 5-hydroxytryptamine metabolism". Biochemical Pharmacology. 19. Elsevier BV: 1181–1188. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(70)90378-3. ISSN 0006-2952.

- ^ Tilson HA, Sparber SB (June 1972). "Studies on the concurrent behavioral and neurochemical effects of psychoactive drugs using the push-pull cannula". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 181 (3): 387–398. PMID 5033008.

- ^ Trulson ME, Crisp T, Henderson LJ (December 1983). "Mescaline elicits behavioral effects in cats by an action at both serotonin and dopamine receptors". Eur J Pharmacol. 96 (1–2): 151–154. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(83)90544-7. PMID 6581976.

- ^ a b Nagai F, Nonaka R, Satoh Hisashi Kamimura K (March 2007). "The effects of non-medically used psychoactive drugs on monoamine neurotransmission in rat brain". European Journal of Pharmacology. 559 (2–3): 132–137. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.075. PMID 17223101.

- ^ Eshleman AJ, Forster MJ, Wolfrum KM, Johnson RA, Janowsky A, Gatch MB (March 2014). "Behavioral and neurochemical pharmacology of six psychoactive substituted phenethylamines: mouse locomotion, rat drug discrimination and in vitro receptor and transporter binding and function". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 231 (5): 875–888. doi:10.1007/s00213-013-3303-6. PMC 3945162. PMID 24142203.

- ^ Smith MV. "Psychedelics and Society". Erowid.org. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b Buckingham J (2014). "Mescaline". Dictionary of Natural Products: 254–260.

- ^ Trachsel D (2012). "Fluorine in psychedelic phenethylamines". Drug Testing and Analysis. 4 (7–8): 577–590. doi:10.1002/dta.413. PMID 22374819. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013.

- ^ Shulgin A. "#157 TMA - 3,4,5-TRIMETHOXYAMPHETAMINE". PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story. Erowid.org. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ Nichols DE (February 1986). "Studies of the relationship between molecular structure and hallucinogenic activity". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 24 (2): 335–340. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(86)90362-x. PMID 3952123. S2CID 30796368.

- ^ Wu D, Otton SV, Inaba T, Kalow W, Sellers EM (June 1997). "Interactions of amphetamine analogs with human liver CYP2D6". Biochemical Pharmacology. 53 (11): 1605–1612. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(97)00014-2. PMID 9264312.

- ^ Cochin J, Woods LA, Seevers MH (February 1951). "The absorption, distribution and urinary excretion of mescaline in the dog". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 101 (2): 205–209. PMID 14814616.

- ^ United States Department of Justice. "Drug Scheduling". Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2007.

- ^ "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2005. Retrieved 27 January 2008.

- ^ "State v. Mooney". utcourts.gov. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Colorado Proposition 122, Decriminalization and Regulated Access Program for Certain Psychedelic Plants and Fungi Initiative (2022)".

- ^ Gupta RC (2018). Veterinary Toxicology: Basic and Clinical Principles (Third ed.). Academic Press. pp. 363–390. ISBN 9780123704672.

- ^ "2007 U.K. Trichocereus Cacti Legal Case Regina v. Saul Sette". Erowid.org. June 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b Poisons Standard February 2020. comlaw.gov.au

- ^ "Justice Laws Search". laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Постановление Правительства РФ от 30.06.1998 N 681 "Об утверждении перечня наркотических средств, психотропных веществ и их прекурсоров, подлежащих контролю в Российской Федерации" (с изменениями и дополнениями) - ГАРАНТ". base.garant.ru.

- ^ Doyle P (20 May 2019). "Patti Smith Channels French Poet Antonin Artaud on Peyote". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "The Father of Flower Power". The New Yorker. 10 August 1968. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Ellis H (1898). "Mescal: A New Artificial Paradise". The Contemporary Review. Vol. LXXIII.

- ^ Rudgley R (1993). "VI". The Alchemy of Culture: Intoxicants in Society. British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1736-2.

- ^ Giannini AJ (1997). Drugs of Abuse (Second ed.). Los Angeles: Practice Management Information Corp. ISBN 978-1-57066-053-5.

- ^ Witkiewicz SI, Biczysko S (1932). Nikotyna, alkohol, kokaina, peyotl, morfina, eter+ appendix. Warsaw: Drukarnia Towarzystwa Polskiej Macierzy Szkolnej.

- ^ "Alexander Shulgin: why I discover psychedelic substances". Luc Sala interview. Mexico. 1996. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021.

- ^ Papaseit E, Farré M, Pérez-Mañá C, Torrens M, Ventura M, Pujadas M, et al. (2018). "Acute Pharmacological Effects of 2C-B in Humans: An Observational Study". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 9: 206. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00206. PMC 5859368. PMID 29593537.

- ^ "Mescaline". Psychedelic Science Review. 2 December 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ Bird M (2012). 100 Ideas that Changed Art. London: Laurence King Publishing.

- ^ Dixit J (23 June 2008). "George Carlin's Last Interview". Psychology Today.

- ^ Greene A (1989). "Dazed and Confused: 10 Classic Drugged-Out Shows". Rolling Stone.

Santana at Woodstock, 1969 - Mescaline

- ^ "Ward Kimball's Final Farewell". cartoonician.com. 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Boardman M (10 July 2013). "Michael Cera Took Drugs On-Camera". Huffington Post.

- ^ "FLOW MY TEARS". www.philipkdickfans.com. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Jay M (2019). Mescaline: A Global History of the First Psychedelic. Yale University Press.

- Klüver H (1942). "Mechanisms of hallucinations." (PDF). In McNemar Q, Merrill MA (eds.). Studies in personality. McGraw-Hill. pp. 175–207.

- Pollan M (2021). This Is Your Mind on Plants. Penguin Press. ISBN 9780593296905.

External links

[edit]- National Institutes of Health – National Institute on Drug Abuse Hallucinogen InfoFacts

- Mescaline at Erowid

- Mescaline at PsychonautWiki

- PiHKAL entry

- Mescaline entry in PiHKAL • info

- Film of Christopher Mayhew's mescaline experiment on YouTube

- Mescaline: The Chemistry and Pharmacology of its Analogs, an essay by Alexander Shulgin

- Mescaline on the Mexican Border